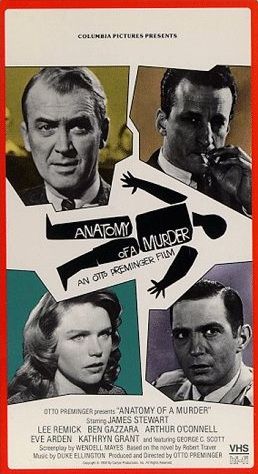

James R. Elkins

"Anatomy of Murder"

(1959)

[Director: Otto Preminger; with James Stewart, Lee Remick, Ben Gazzara, Arthur O'Connell, Eve Arden, George C. Scott, & Joseph Welch]

[Running time: 160 minutes]

[Music: Duke Ellington]

[Wendell Mayes screenplay]

[adapted from the novel by Robert Traver]

Hallmark Qualities: Robert McKee, in Story: Substance, Structure, Style, and the Principles of Screenwriting (1998), argues that all film protagonists must have "certain hallmark qualities":

–"a willful character"

– "a conscious desire" ( the protagonist "may also have a self-contradictory unconscious desire"

– "capacities to pursue the Object of Desire convincingly"

– "a chance to attain his desire"

– "the will and capacity to pursue the object of his conscious and/or unconscious desire to the end of the line, to the human limit established by setting and genre." [136-141].

In what sense does Paul Biegler satisfy or defy McKee's "hallmark qualities" as a protagonist?

Story Premise and Arc of the Film: What is the story premise of this film? A story premise depends upon what Robert McKee calls the "arc of the film."

When you look at the value-charged situation in the life of the character at the beginning of the story, then compare it to the value-charge at the end of the story, you should see the arc of the film, the great sweep of change that takes life from one condition at the opening to a changed condition at the end. [Robert McKee, Story: Substance, Structure, Style, and the Principles of screenwriting 41 (New York: HarperCollins/Regan Books, 1998)]

McKee goes on to note that there is a kind of film which is characterized by its “nonplot”: “. . . stories remain in stasis and do not arc. The value-charged condition of the character’s life at the end of the film is virtually identical to that at the opening. Story dissolves into portraiture . . . .” [57-58]. “Although nothing changes within the universe of Nonplot, we gain a sobering insight and hopefully something changes within us.” [58]

Ordinary and Special Worlds: Compare the opening scenes in “Adam’s Rib” and “Anatomy of a Murder.”

– “Adam’s Rib” begins in the spacious, sun-filled bed room–the domestic sanctuary–of Amanda and Adam Bonner.

– “Anatomy of a Murder” begins with Paul Biegler returning from a fishing trip, to clean fish in his house, where we get the first look at his home that is used for a law office. We don’t see any law books in the bedroom or anywhere in the apartment of Adam and Amanda Bonner, but they do have a fancy party in which judges are invited, and there’s a good deal made of this fact.

Note1: Adam and Amanda Bonner communicate with each other beneath counsel tables, and they do this twice during the course of the trial. We see something of a similar sort in “Anatomy of a Murder” when Paul Biegler works on one of his frog lures during the trial, and, to the annoyance of the D.A. and the Asst. State Atty. General Claude Dancer, Biegler has a friendly conversation with Judge Weaver about the use of the lures. [Judge Weaver is played by Joseph Welch, the attorney for the Army in the McCarthy hearings. On Joseph McCarthy: Joseph McCarthy]

Note2: Robert McKee observes that: "Limitation is vital. The first step toward a well-told story is to create a small, knowable world.” [71] “All fine stories take place within a limited, knowable world. No matter how grand a fictional world may seem, with a close look you’ll discover that it’s remarkably small.” [71] “A ‘small’ world, however, does not mean a trivial world. Art consists of separating one tiny piece from the rest of the universe and holding it up in such a way that it appears to be the most important, fascinating thing of this moment. ‘Small,’ in this case, means knowable.” [72]

Mentors and Helpers: What role does Biegler's buddy and lawyer colleague, Parnell McCarthy, play in the film? Christopher Vogler, in The Writer's Journey, points out that "[t]he relationship between hero and Mentor is one of the most common themes in mythology. . . ." [17] [On the mentor, see Christopher Vogler, The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers 38-47, 117-125 (Studio City, California: Michael Weise Productions, 3rd ed., 2007)] . We probably wouldn't think of McCarthy as a mentor as that term is used today, but as an old friend and colleague, or to use a more colloquial expression, a "side-kick." Vogler says the function of the Mentor is "to prepare the hero to face the unknown." [18]. In what way does McCarthy help Biegler "face the unknown"?

McCarthy has a drinking problem. How does his problem become a backstory in the film? [Robert Traver, in another novel, Laughing Whitefish 43 (McGraw-Hill Book Co., 1965) has one of the book's lawyer characters, Cassius Wendell, another drinker, observe: "I suppose really . . . all periodic drunkards have a secret sorrow and keep thinking with whiskey I can buy forgetfulness."]

Backstory: McKee, in Story: Substance, Structure, Style, and the Principles of Screenwriting makes reference to the backstory which is the "set of significant events that occurred in the characters' past" that figure in the present drama. [McKee, at 183]. What backstory (or stories) help define the protagonist, Paul Biegler, in "Anatomy of a Murder"?

The Lieutenant's Wife: Early in the film, Paul Biegler talks with Laura Manion, Lt. Manion's wife about the possibility of representing her husband. How does Biegler deal with Laura Manion? What kind of problem does she represent?

Ethics and Story Creation: Paul Biegler's first conversations with his new client, Lt. Manion, at the jail are often referred to as the "coaching scenes." These scenes, and what Biegler's fellow lawyer, Parnall, calls "the lecture," are well known in legal ethics circles. What kind of ethical line must be drawn in this situation? How does Biegler struggle to draw this line? [On "the lecture," see: Michael Asimow]

Attorney-Client Relationships: What kind of relationship does Paul Biegler have with his client? How would you characterize the early scenes in the film where Paul Biegler interviews his new client, Lt. Manion, at the jail?

On the attorney-client relationship in films, see: J. Thomas Sullivan, Imagining the Criminal Law: When Client and Lawyer Meet in the Movies, 25 U. Ark. L. Rev. 655 (2003)

Judges in Lawyer Films: Compare the portrayal of the judge in "Anatomy of a Murder" with the judge in "Adam's Rib."

[On the portrayal of judges in films, see: David Ray Papke, From Flat to Round: Changing Portrayals of the Judge in American Popular Culture]

Pace of the Film: "Anatomy of a Murder" is hardly an action/thriller and it turns out not to be a mystery. We know early on that Lt. Manion killed Barney Quill, and for all intents and purposes, that he did it in a premeditated fashion. What we don't know is whether Paul Biegler will be successful in securing an acquittal although it becomes apparent early on that he is going to give it his best effort. I think it can be said that the film does not turn on the outcome of the trial, and the uncertainty as to the outcome does not provide the dramatic tension in the film.

We know early on that Paul Biegler cares deeply about his friend Parnell McCarthy, and that Parnell has a drinking problem. Biegler doesn't seem particularly worried about his friend, and so the viewer is lulled into assuming that Parnell will not let his friend down.

What, then, one might ask, provides dramatic tension in "Anatomy of a Murder"?

For some viewers, awash in action films and thrillers, there is far too little dramatic tension. One viewer on the Internet Movie Data Base, asks: "Engrossing, but why did it have to be so long?" ("Anatomy of a Murder" runs for 2 hrs. & 40 minutes.) According to Matt Zoller Steiz, Otto Preminger, the film's director, has "eschewed the hustling, high-voltage approach." Noel Murray, in a synopsis for the Nashville Scene complains of the film's "sluggish midsection. Steiz notes that Preminger puts "almost equal stress on dramatic high points and the quieter moments in between." Edwin Jahiel in his review of the film says, "Preminger treats his movie with almost glacial objectivity."

Robert McKee, in Story: Substance, Structure, Style, and the Principles of Screenwriting, talks about pacing [289-291] and it may be in the pacing of "Anatomy of a Murder" that viewers find insufficient action to justify the length of the film. McKee argues that every film need not present the kind of tension that mounts scene by scene until the climax. Rather, "a story is a metaphor for life," a point that McKee makes throughout the book, and so a story must have "the rhythm of life."

This rhythm beats between two contradictory desires: On one hand, we desire security, harmony, peace, and relaxation, but too much of this day after day and we become bored . . . . As a result, we also desire challenge, tension, danger, even fear. But too much of this day after day and again we end up in the rubber room. So the rhythm of life swings between these two poles. [289]

This alternation between tension and relaxation is the pulse of living, the rhythm of days, even years. In some films it's salient, in others subtle. [290]

How would you describe the subtleties of pacing in "Anatomy of a Murder"?

Conflict: McKee argues that "deep within" the film's principle characters "we discover our own humanity.” [5] Can this be said of the characters in "Anatomy of a Murder"?

Law as a Character in Lawyer Films: How is the Law represented in this film?

We find in “Anatomy of a Murder” another reference to the “unwritten law.” Lt. Manion’s idea that according to the “unwritten law” a man can shoot and kill a man who has raped his wife. Paul Beigler tells Manion that “The unwritten law is a myth.”

Duke Ellington's Film Score as a "Character" in the Film: If, as I have suggested, Law becomes a character in a lawyer film, would it be accurate to say that Duke Ellington's music is a "character" in this film?

[Duke Ellington, "Anatomy of a Murder," (Sony/Columbia Audio CD, 1999)] [sample tracks from amazon.com] [One reviewer says, of Ellington's music score: "The sheer energy and dynamism in every cue is incredibly infectious."]

Ellington composed the film score for the film and has a cameo appearance in the film as "Pie-eye," a jazz musician in a bar that Paul Biegler frequents.

A Lawyer and His Interest in Music: What do you make of Laura Manion’s statement to Biegler, “You’re a funny kind of lawyer. The music and all.”

Archetypal Stories: Robert McKee notes that: “The archetypal story unearths a universally human experience, then wraps itself inside a unique, culture-specific expression.” [4] In what sense is "Anatomy of a Murder" an "archetypal story" as McKee uses that term? McKee goes on to note: “An archetypal story creates settings and characters so rare that our eyes feast on every detail, while its telling illuminates conflicts so true to humankind that it journeys from culture to culture to culture.” [4]

Stories and Values: “Values are the soul of storytelling. Ultimately ours is the art of expressing to the world a perception of values.” [McKee, at 34]

Bibliography

"Anatomy of a Murder," in Paul Bergman & Michael Asimow, Reel Justice: The Courtroom Goes to the Movies 232-238 (Kansas City: Andrews & McMeel, 1996)

Omit Kamir, Towards a Theory of Law-and-Film: A Case Study of Hollywood's Hero-Lawyer and the Construction of Honor and Dignity (2004) [online text] [citation: Omit Kamir, Anatomy of Hollywood's Hero-Lawyer: A Law-and-Film Study of Western Motifs, Honor-Based Values and Gender Politics Underlying "Anatomy of a Murder's" Construction of the Lawyer Image, 35 Studies in Law, Politics & Society 35 (2004)]

"'Anatomy of a Murder' (U.S.A., 1959): Hollywood’s Hero-Lawyer Revives the

Unwritten Law," in Omit Kamir, Framed: Women in Law and Film 112-159 (Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2006)

Misc. Notes

![]() Robert Traver: Robert Traver is the pseudonym of Michigan judge, fly-fisherman, and novelist, John Voelker.

Robert Traver: Robert Traver is the pseudonym of Michigan judge, fly-fisherman, and novelist, John Voelker.

John Voelker

Michigan Supreme Court Historical SocietyVoelker Collection

Northern Michigan University

![]() Writings

of Robert Traver: "Anatomy of a Murder" is adapted from

a novel by John D. Voelker, who wrote the book using the pen name Robert Traver: Anatomy of a Murder (New York: St. Martin's

Press, 1958). Voelker said of Anatomy of a Murder: It "was

not only my first courtroom novel but my first novel ever—written

after I was 50. I should confess, so my fellow slow-starting lawyer-writers

might not too easily despair. And I call its success surprising for that

it most surely was. After all, my three earlier books had set some sort

of track record in becoming collector's items—just collector's items,

to be more precise." [Robert Traver, Buried Courtroom

Tales, 68 ABA J. 1104 (September, 1982)]

Writings

of Robert Traver: "Anatomy of a Murder" is adapted from

a novel by John D. Voelker, who wrote the book using the pen name Robert Traver: Anatomy of a Murder (New York: St. Martin's

Press, 1958). Voelker said of Anatomy of a Murder: It "was

not only my first courtroom novel but my first novel ever—written

after I was 50. I should confess, so my fellow slow-starting lawyer-writers

might not too easily despair. And I call its success surprising for that

it most surely was. After all, my three earlier books had set some sort

of track record in becoming collector's items—just collector's items,

to be more precise." [Robert Traver, Buried Courtroom

Tales, 68 ABA J. 1104 (September, 1982)]

Traver's other writings include:

The Dictionary and Jim Darneal, 64 Michigan Bar Journal 414 (May 1985)

A Jury of Your Peers, 63 Michigan Bar Journal (May, 1984)

Trout Magic (Salt Lake City: Peregrine Smith Books, 1983)

Big Secret Trout, 89 American Forests 34 (August, 1983)

Buried Courtroom Tales, 68 American Bar Association Journal 1104 (September, 1982)

People versus Kirk (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1981)

The Jealous Mistress (Boston: Little, Brown, 1968) (1967)

Laughing Whitefish (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1965)

Hornstein's Boy (New York, St. Martin's Press, 1962)

Anatomy of a Fisherman (New York: Mc-Graw-Hill, 1964)

Small Town D.A. (New York: Dutton, 1954)

Danny and the Boys : Being Some Legends of Hungry Hollow (Detroit : Wayne State University Press, 1987) (1951)

Trouble-Shooter: The Story of a Northwoods Prosecutor (New York: Viking Press, 1943)

![]() Commentary on Traver|Voelker and the Historical Context of His Writing: "After losing re-election as District Attorney of Marquette County and a later congressional bid, he had turned to a criminal defense practice. During a dismal winter when clients were sparse he decided to write a courtroom drama that really showed what lawyers did, both in their offices and the courtroom. He pitted a small-town hero against an out-of-town hired-gun prosecutor in the trial of a bigoted and violent man, who seemed to have defended his wife's honor with murder. Voelker's careful attention to correct legal procedure and the cynical finale raised a new standard for future legal thrillers.

Commentary on Traver|Voelker and the Historical Context of His Writing: "After losing re-election as District Attorney of Marquette County and a later congressional bid, he had turned to a criminal defense practice. During a dismal winter when clients were sparse he decided to write a courtroom drama that really showed what lawyers did, both in their offices and the courtroom. He pitted a small-town hero against an out-of-town hired-gun prosecutor in the trial of a bigoted and violent man, who seemed to have defended his wife's honor with murder. Voelker's careful attention to correct legal procedure and the cynical finale raised a new standard for future legal thrillers.

"Anatomy did not begin a trend. Lawyers were too busy practicing law and making money. The 1950s, like the '20s, saw tremendous growth in transactional work for attorneys. It wasn't until the 1970s, and especially the '80s, that lawyers once again began to turn away from their practices to write fiction, bringing a new edge of realism and authority to mysteries engaging the law. The boom in legal business up to the late '80s was accompanied by a massive burn-out. Intense pressure for billing hours, competition for those hours, and a general feeling that law was not nearly so exciting as they had thought during law school caused a large number of lawyers to rethink their careers. The economic bust of the late '80s saw many lawyers casting about for alternative careers. Then in 1987, Scott Turow's success with Presumed Innocent exploded the legal thriller market. The sheer number of lawyer/authors dictates that the major characteristic of the genre in this decade is enormous diversity in writing styles, themes and series characters." [Maryln Robinson, Collins to Grisham: A Brief History of the Legal Thriller, 22 Legal Studies Forum 21 (1998)]

[For commentary on Traver's writings, see: Joseph V. Wilcox, From Supreme Court to Frenchman's Pond: Robert Traver, 63 Mich. B. J. 341 (May, 1984); William Domnarski, Book Review (People versus Kirk), 59 Virginia Quart. Rev. 525 (1983)]

In the preface to Small Town D.A., a collection of stories about his years as a prosecuting attorney in Michigan, Traver notes:

Fourteen years is a long time to survive as D.A., an occupation with a high electoral mortality rate. Since nearly every young lawyer in America who ever recited A Message to Garcia in high school aspires to D.A., naturally at every election there is a mad scramble for the job. All during my time in office a small regiment of these aspiring youngsters pursued me, baying and snapping at my heels. At last political arthritis set in and one of them finally brought me down.

. . . . I liked being D.A. and I loved—and still love—living full-time in my native Upper Peninsula. A clue to my eccentricity perhaps lies in the fact that the U.P.—besides being a wildly beautiful place—possesses three of Nature's noblest creations: the white-tailed deer, the ruffed grouse and the brook trout. I photograph the deer, mildly hunt the partridge, and endlessly pursue the elusive trout. . . .

The D.A. is inevitably in daily collision with life at its most elemental level. His job is somewhat akin to that of a young intern on Saturday night ambulance call: he is constantly witnessing the naked emotions of his people—raw, unbuttoned and bleeding. His is a tremendous experience with life itself, and he must leave his job either a better man or a lethargic bum. There is no middle way. [Robert Traver, Small Town D.A. 10-11 (New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., 1954)]

![]() Stage Adaptation: Elihu Winer, Anatomy of a Murder: A Court-Drama in Three Acts (New York: S. French, 1964) (based on the novel by Robert Traver)

Stage Adaptation: Elihu Winer, Anatomy of a Murder: A Court-Drama in Three Acts (New York: S. French, 1964) (based on the novel by Robert Traver)

![]() On

the Allure of Fly-Fishing & Fishing Stories: Traver said

of his fishing: "During my 40-odd years of lawyering, writing, and

trout fishing, I have haunted a lot of courtrooms, scrawled countless reams

of words, and—this, I swear—waded at least the length of the

Mississippi in pursuit of the elusive trout."

[Robert Traver, Buried Courtroom Tales, 68 ABA J. 1104 (September, 1982)].

For the penultimate lawyer/fishing story, see John William Corrington,

A Day in Thy Court, 26 Legal Studies Forum 336 (2002).

On

the Allure of Fly-Fishing & Fishing Stories: Traver said

of his fishing: "During my 40-odd years of lawyering, writing, and

trout fishing, I have haunted a lot of courtrooms, scrawled countless reams

of words, and—this, I swear—waded at least the length of the

Mississippi in pursuit of the elusive trout."

[Robert Traver, Buried Courtroom Tales, 68 ABA J. 1104 (September, 1982)].

For the penultimate lawyer/fishing story, see John William Corrington,

A Day in Thy Court, 26 Legal Studies Forum 336 (2002).

![]() George C. Scott: George C. Scott's portrayal of Claude Dancer, an Assistant Attorney General, who assists the local prosecutor in the Manion murder trial was only his second role. Paul Riordan, in a review of Scott's films, applauds Scott's "strong performance" and his ability to "hold[] his own with such veterans as Jimmy Stewart." Scott told Riordan: "They originally wanted me to play the bartender," Scott said, "but I told them I wanted to play the guy from Lansing. So, they gave me that part, and Murray Hamilton ended up playing the bartender." [Paul Riordan, The Films of George C. Scott]

George C. Scott: George C. Scott's portrayal of Claude Dancer, an Assistant Attorney General, who assists the local prosecutor in the Manion murder trial was only his second role. Paul Riordan, in a review of Scott's films, applauds Scott's "strong performance" and his ability to "hold[] his own with such veterans as Jimmy Stewart." Scott told Riordan: "They originally wanted me to play the bartender," Scott said, "but I told them I wanted to play the guy from Lansing. So, they gave me that part, and Murray Hamilton ended up playing the bartender." [Paul Riordan, The Films of George C. Scott]

![]() James Stewart: Tribute to Jimmy Stewart

James Stewart: Tribute to Jimmy Stewart

![]() Otto Preminger: Preminger, interestingly enough, had a law degree.

Otto Preminger: Preminger, interestingly enough, had a law degree.

![]() Reviews and Film Commentary

Reviews and Film Commentary

Hall Movie.com film blurb: "Acclaimed, groundbreaking adult courtroom drama focuses on a crime of passion. With its masterful direction, stellar cast, and swinging score, this is still a hit with drama, suspense, classics buffs."

From Film Vault/Nashville Scene: "That boldness of approach—combined with a fresh score by Duke Ellington and electrifying performances by Lee Remick and a young George C. Scott—sticks in the mind more than the film's sluggish midsection. Credit Stewart again for doing the film's dirty work: holding our attention as a sweet-natured defense attorney and then shocking us with how hard-edged and aloof he can become while discussing the condition of a victim's panties. That edginess startles Scott as well, and the war of words between the two attorneys provides some of the greatest courtroom sparks this side of Inherit the Wind."

Many film critics contend that "Anatomy of a Murder" is one the best courtroom dramas every filmed.

Austin Chronicle Movie Guides Scanlines

Amazon.com

viewer's commentary

![]() American Film Institute|Commentary|Videos

American Film Institute|Commentary|Videos

Leonard Matlin ![]() Talia Shire

Talia Shire ![]() Ben Gazzara

Ben Gazzara

![]() Academic Writings on "Anatomy of a Murder"

Academic Writings on "Anatomy of a Murder"

Timothy Hoff, Anatomy of a Murder, 24 Legal Studies Forum 661 (2000)

"Anatomy of a Murder," in Thomas J. Harris, Courtroom's Finest Hour in American Cinema 68-109 (Metuchen, New Jersey: Scarecrow Press, 1987)

"The Adversary System and the Courtroom Genre ["Anatomy of a Murder"]," in Michael Asimow & Shannon Mader, Law and Popular Culture: A Course Book 17-29 (New York: Peter Lang, 2004)

Anthony Chase, Movies on Trial: The Legal System on the Silver Screen 8-9, 10 (New York: The New Press, 2002)

Frederick Baker, Jr., "An Anatomy of Anatomy of a Murder" (address to the National Conference of Chief Justices, 2007) [on-line text]

Orit Kamir, "Anatomy of Hollywood’s Honorable Hero-Lawyer: A Law-and-Film Study of the Western Motifs, Honor-Based Values and Gender Politics Underlying Anatomy of a Murder’s Construction of the Lawyer Image"

Nina W. Tarr, A Different Ethical Issue in Anatomy of a Murder: Friendly Fire From the Cowboy-Lawyer, 32 J. Legal Profession 137 (2008)

![]() Misc. Web Resources

Misc. Web Resources

![]() Other

Notable Legal Films of 1959: "The Young Philadelphians"

(starring Paul Newman)

Other

Notable Legal Films of 1959: "The Young Philadelphians"

(starring Paul Newman)