James R. Elkins

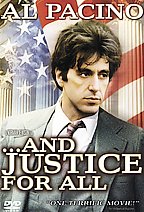

"And Justice For All"

(1979)

Law and Lawyers and the World Around Them: What kind of change do you see reflected in the worlds depicted in "Adam's Rib" and "Anatomy of a Murder" and the world portrayed in "And Justice for All"?

How does the world in which we find ourselves affect the way a lawyer tries to practice law?

James Berardinelli, in a review of "And Justice for All," points out that "Once, practicing law was considered a worthy, honorable career. No longer. In a bloated legal system where technicalities count more than justice, and where wealth and fame can buy freedom, lawyers have become the parasites who feed off the desiccated remains of human suffering. To be sure, there are some who still enter the profession with the best of motives, but they are in the minority. Law is not about idealism; it's about money and back-room deals." Berardinelli says "And Justice for All," with its "bleak, absurd look at lawyers" and shaped by elements of satire and black comedy, "would be hilarious if it wasn't so true-to-life."

One might wish for a more nuanced, and carefully argued statement as to the nature of the problem we face in the legal profession, but Berardinelli's point, too easily dismissed as a gross exaggeration, need not be dealt with by dismissal, denial, or defensiveness. We need to reflect on this question: What does it mean, to enter a profession, which is so easily characterized by the views expressed by Berardinelli?

Even if Berardinelli over paints his canvas, isn't there a critique of law and the legal system lurking in "And Justice for All"?

Anti-lawyer Films: Some academics, film reviewers, and law-trained viewers of films consider films like "And Justice for All" and "Devil's Advocate," films that portray the dark, shadow world of our profession, to be anti-lawyer. How are we to read lawyer films in which law and lawyers are portrayed as accomplices in what James Berardinelli refers to as "deeply-rooted hypocrisy and cynicism that defines American law"?

One problem with this notion of films as being anti-lawyer is that the films in which negative elements of the profession are portrayed also present lawyers, like Arthur Kirkland (in "And Justice for All"), who passionately care for their clients, fight for them at every turn, and are willing to risk their careers to maintain his own integrity in a world where law destroys or devours everything it touches. If today's lawyer films are anti-lawyer, how do we explain a lawyer like Arthur Kirkland?

Conflict: What is the nature of the conflict represented in "And Justice for All"? What conflict in law do we find presented?

Kirkland says of Judge Fleming: "This Judge Fleming goes by the letter of the law." The problem is that Kirkland's client, Jeff, is innocent and by upholding the law the judge sanctions a cruel injustice. Arthur Kirkland seems troubled in ways that Gail Packer (and Warren, the lawyer who takes the probation hearing for Arthur when he ministers to his friend Jay) are not. The pay-off from following conventional views is that we are more insulated from the world around us. Arthur Kirkland sees/knows/understands the world in a way that leads, at the end of the film, to an unconventional, career-threatening stance, to recognize the truth in a world of lies and deception.

Opening Scenes: The opening scenes of a film are important—and thus, the abhorrence of dedicated film buffs at arriving late and missing the opening moments of the film.

"To Kill a Mockingbird" opens with the the beautiful presentation of objects and a child drawing. We later learn that these objects have been found by Jem Finch in the knothole of a tree, objects placed there by the reclusive Boo Radley. The objects intrigue the children and are hidden away so that their father will not learn they have them. These objects are Boo Radley's link to these children he admires from a secluded distance.

In "And Justice for All" there is a voice-over of young children reciting the Pledge of Allegiance, making mistakes as young children will do, but earnest, and passionate in their efforts to get it right. As we listen to these children and their recitations the camera walks us up the steps of an official building, the jail in which we are introduced to the lawyer, Arthur Kirkland.

Gail Packer: Gail Packer, the lawyer on the ethics committee, is according to one student, "the voice of reason." I think of her as the "voice of convention."

Arthur Kirkland tells Gail: "You're conning the public. You're skimming the surface. You're not going after the real power." Isn't there some pernicious mischief on the part of those who are eager to punish minor wrongdoers when serious corruption goes unchallenged? Shouldn't one be concerned that our criminal justice system seems more intent and efficient in locking up drug offenders than in prosecuting complex, white-collar, corporate crime?

The Lawyer as Hero: See, Frank McConnell, Storytelling and Mythmaking: Images From Film and Literature 14 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979): “[T]he hero of melodrama, the detective, the investigator, the inquisitive person desperate to find out how a confusing and corrupt society operates, may become a more bitter figure. He may become the investigator who has discovered that everyone is guilty, the detective who finds that the City itself is the criminal he pursues, since the City has failed to live up to the moral sanctions envisioned by its epic founders. The hero, in other words, is now the satirist: his relationship to the community is that of prophetic scorn, disdain, even visionary paranoia. And the City, the community, is now inimical to the survival of the individual, rather than a means of that survival.”

“Of course, depending upon how many of his audience share his concern with the decay of the epic foundations of the city, the satirist will tend toward either the position of an officially recognized public voice or that of a lone, crazed prophet crying in the wilderness.” [Id.]

And then, in still a new phase of the satirist/prophet, “[t]he hero is no longer public moral voice or crazed prophet, that is, but lives between the riskier alternatives of Messiah or madman.” [15]

![]() Bibliography

Bibliography

", , , And Justice for All," in Paul Bergman & Michael Asimow, Reel Justice: The Courtroom Goes to the Movies 109-113 (Kansas City: Andrews & McMeel, 1996)

![]() Attorney's Disclosure of a Client's Confidence: The primary

reason that Arthur Kirkland is blackmailed into representing Judge Fleming

is Judge Rayford's suggestion that Kirkland might be subject to disbarment

for the disclosure of a client's confidence. If Kirkland's action in revealing

information that he knew about a former client was evaluated under Rule

1.6 (b), Model Rules of Professional Conduct, it's not at all clear that

he committed an ethical violation. [Rule

1.6, Model Rules of Professional Conduct]

Attorney's Disclosure of a Client's Confidence: The primary

reason that Arthur Kirkland is blackmailed into representing Judge Fleming

is Judge Rayford's suggestion that Kirkland might be subject to disbarment

for the disclosure of a client's confidence. If Kirkland's action in revealing

information that he knew about a former client was evaluated under Rule

1.6 (b), Model Rules of Professional Conduct, it's not at all clear that

he committed an ethical violation. [Rule

1.6, Model Rules of Professional Conduct]

![]() Film Basics

Film Basics

![]() Reviews: Roger Ebert

Reviews: Roger Ebert ![]() DVD Times

DVD Times

![]() YouTube videos: Trailer

YouTube videos: Trailer

![]() Al Pacino: Interview: Good Morning America

Al Pacino: Interview: Good Morning America