James R. Elkins

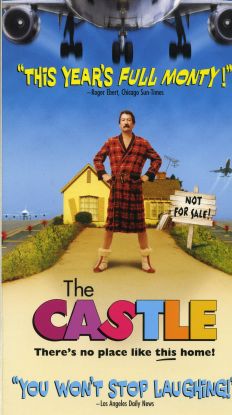

"The Castle"

(1997)

![]() Michael Asimow, a UCLA law professor and film critic, notes that he found the film "funny—I mean, really funny" but goes on to note: "But funny in the best way, like The Full Monty or My Cousin Vinny, it's affectionate toward its characters and it's about something serious." [Return of the Heroic Lawyers . . . And the Heroic Clients: The Winslow Boy and The Castle, a commentary that appeared on the "Picturing Justice" website that is now defunct]

Michael Asimow, a UCLA law professor and film critic, notes that he found the film "funny—I mean, really funny" but goes on to note: "But funny in the best way, like The Full Monty or My Cousin Vinny, it's affectionate toward its characters and it's about something serious." [Return of the Heroic Lawyers . . . And the Heroic Clients: The Winslow Boy and The Castle, a commentary that appeared on the "Picturing Justice" website that is now defunct]

When Asimow says "The Castle" is "about something serious" what do you think he has in mind?

![]() I've never quite seen the wisdom in the well-worn expression "beauty lies in the eye of the beholder." Yes, it presents a partial truth—we don't have any ultimate authoritative guide to what constitutes beauty and in all things human there are differences—but it's an expression that more commonly does damage to our commonly-held notions of beauty than it has ever done in establishing the subjective nature of beauty.

I've never quite seen the wisdom in the well-worn expression "beauty lies in the eye of the beholder." Yes, it presents a partial truth—we don't have any ultimate authoritative guide to what constitutes beauty and in all things human there are differences—but it's an expression that more commonly does damage to our commonly-held notions of beauty than it has ever done in establishing the subjective nature of beauty.

I get better mileage from this worn-out expression about beauty when I apply it to humor—humor seems far more than beauty to be a matter of individual preference. Humor, far more than beauty, lies on knife's edge; it can fall one way or the other. When it falls the wrong way, it can be laborious and boring. Does the humor of "The Castle" work for you? And if so, can you articulate why?

![]() What part do comedy films like My Cousin Vinny and The Castle have in the lawyer film genre?

What part do comedy films like My Cousin Vinny and The Castle have in the lawyer film genre?

[See, Michael Asimow, Film Commentary, 24 Legal Stud. F. 335, 337 (2000)][On the use of “pranks” in legal films, see Paul Bergman, Pranks for the Memory, 30 USF L. Rev. 1235 (1996)(suggesting the linkage of the lawyer as prankster/trickster to pranks commonly found in legal films, but failing to draw the larger cultural meaning of the trickster). See also, Robert M. Jarvis, “Situation Comedies,” in Robert M. Jarvis & Paul R. Joseph (eds.), Prime Time Law Fictional Television as Legal Narrative 167-179 (Durham, North Carolina: Carolina Academic Press, 1998).On seeing the humor in our affinity for law, see Alex Kozinski, How I Narrowly Escaped Insanity, 48 UCLA L. Rev. 1293 (2001)]

![]() Bill Johnson in A Story is a Promise (2000) talks about how

stories fill a need. What need does the story in "The Castle"

fill?

Bill Johnson in A Story is a Promise (2000) talks about how

stories fill a need. What need does the story in "The Castle"

fill?

I wonder whether the need in this story isn't related to the ever constant need to deal in some emotional way with the smallness we experience in a world of largeness, a world in which large can mean alluring freedom but can also mean overwhelming and devouring. The Kerrigans, whatever their illusions of being part of the large world, are largely ignorant of it. Their ignorance represents innocence. Ignorance is often the basis of cruelty and prejudice, but we don't see anything of that sort on the part of the Kerrigans. When we see how the small world they have created for themselves works, we pity them at our peril. Indeed, we may even admire them. They seem to be resourceful, caring, neighborly, open, curious, affectionate, accepting, and even courageous. They listen to each other and enjoy each other's company. There is so much to like about the Kerrigans that we begin to overlook just how odd they are; Darryl Kerrigan takes great pleasure in the massive power lines stretched across his property, enjoys the smell of diesel fuel in the air at his lake property, and finds great wonder in his wife's simple cooking.

Dennis Denuto, the lawyer who Darryl Kerrigan drags into his case, is a small man and, interestingly enough, he knows it. He lays out quite clearly his place in the legal pecking order, telling Darryl: "I'm not in the big time." Denuto also has a clear picture of the situation and the magnitude of what Darryl Kerrigan wants him to do. He knows he's a little fish in a big pond, that big fish like the Barlow Group which seeks to build the freight terminal at Melbourne International Airport is "used to getting their way"; they'll consume the Kerrigans easily enough. .

We've seen the ordinary worlds depicted in the home life of Adam and Amanda Bonner ("Adam's Rib") and the law office/home of Paul Biegler ("Anatomy of a Murder"). In these films, as well as "Music Box" we see something of the ordinary worlds in which lawyers live, but in "The Castle" we find an ordinary world that seems to have imploded. The Kerrigans are so mired in ordinariness that it has come to define them, in a way that we have not seen in any other film. In "The Castle" we see not just the little man pitted against the brute corporate world—a common enough motif and one of which we seem never to grow tired—but ordinariness of such a totally defining sort that it seems like a great feat when Darryl Kerrigan steps up to save his home from the Australian equivalent of eminent domain.

If "The Castle" spoofs ordinariness—as I think it does—making it a central feature of the story, aren't we being asked to examine our own ordinariness and our efforts to escape it. Mareth Stone, a divorce client of a lawyer named D.T. Jones in a novel called The Ditto List (1985) tells her lawyer she hates being in his office. When he asks why, she replies, "Because it's so common. Every woman I know is divorced, I was so determined it wasn't going to happen to me. But apparently I'm about to join the pack." [The Ditto List, at 33-34]. Doesn't a film—a good one—help us, if only for a few hours, escape that nauseating feeling of commonness that Mareth Stone has articulated to her lawyer?

![]() "The Castle" is a good film to study the process by which

we identify with a character and are seduced into caring about what

happens to that character. As lawyers, we want to be students of character

and character identification because we are often placed in a position

in which we are asking decision-makers to identify with our client.

We try to persuade decision-makers (jurors, judges, other lawyers)

that the law compels a decision in favor of our client, but we know,

that legal decision-makers are human beings and are more likely to

see the law as requiring a decision in favor of a party with whom

we can identify.

"The Castle" is a good film to study the process by which

we identify with a character and are seduced into caring about what

happens to that character. As lawyers, we want to be students of character

and character identification because we are often placed in a position

in which we are asking decision-makers to identify with our client.

We try to persuade decision-makers (jurors, judges, other lawyers)

that the law compels a decision in favor of our client, but we know,

that legal decision-makers are human beings and are more likely to

see the law as requiring a decision in favor of a party with whom

we can identify.

Why do we (and here I may speak only for myself) identify with Darryl Kerrigan and his efforts to save his house at 3 High View Crescent from an expansion of the Melbourne International Airport to build a freight terminal?

![]() Bill Johnson notes that a character in a story engages our attention

because the character is about to resolve an issue of human need.

When we talk about resolving a human need, it should be clear that

we are talking about tackling a problem, confronting an issue, learning

how the world works, acting with courage. We are not, always, or necessarily,

talking about winning, prevailing, getting ahead, meeting career objectives,

or being viewed by others as successful. Darryl Kerrigan in "The

Castle" does happen to prevail, but I don't think it was necessarily

the fact he won his case that creates the bond a viewer has with Darryl

Kerrigan.

Bill Johnson notes that a character in a story engages our attention

because the character is about to resolve an issue of human need.

When we talk about resolving a human need, it should be clear that

we are talking about tackling a problem, confronting an issue, learning

how the world works, acting with courage. We are not, always, or necessarily,

talking about winning, prevailing, getting ahead, meeting career objectives,

or being viewed by others as successful. Darryl Kerrigan in "The

Castle" does happen to prevail, but I don't think it was necessarily

the fact he won his case that creates the bond a viewer has with Darryl

Kerrigan.

![]() Bill Johnson argues that we want to know what's at stake in a story.

("The storyteller provides a clear indication at the outset that

something of consequence is at stake that a story's characters feel

compelled to resolve.") We identify with characters and situations

in which there is clearly something at stake and we are intrigued

by how the characters deal with the serious matters at hand. The Kerrigans

may, from one perspective be thoroughly goofy, but they are a real

family, with what seems to be nothing but pure affection for each

other (especially notable here is Darryl Kerrigan's care for his

neighbors). What is at stake in "The Castle" is not just

one man's house and home, but the fact that our families and neighborhoods

are under threat from just the kind

of forcesthat Darryl Kerrigan faces. The

Kerrigan fight is not isolated or unusual; at stake is not just where

we live but how we live and where our ultimate values lie.

Bill Johnson argues that we want to know what's at stake in a story.

("The storyteller provides a clear indication at the outset that

something of consequence is at stake that a story's characters feel

compelled to resolve.") We identify with characters and situations

in which there is clearly something at stake and we are intrigued

by how the characters deal with the serious matters at hand. The Kerrigans

may, from one perspective be thoroughly goofy, but they are a real

family, with what seems to be nothing but pure affection for each

other (especially notable here is Darryl Kerrigan's care for his

neighbors). What is at stake in "The Castle" is not just

one man's house and home, but the fact that our families and neighborhoods

are under threat from just the kind

of forcesthat Darryl Kerrigan faces. The

Kerrigan fight is not isolated or unusual; at stake is not just where

we live but how we live and where our ultimate values lie.

Lawyers do important work because they work closely (and personally) for individuals and groups where there is much at stake. Isn't this why we cringe at the inept efforts of Dennis Denuto, the local lawyer that Darryl Kerrigan persuades to take on his case? Denuto, initially, seems to have a clear sense about what is at stake and declines to represent Darryl and his neighbors. He tells Darryl, "this is not my area" and he is forthright in his assessment of his practice "I just do small stuff." When Darryl reminds Dennis that he represented his son, Wayne, in a criminal matter. Dennis says, "Yes, and he got eight years." We see something of the depth of Darryl Kerrigan's character when he replies, "Yea, but you did your best." In a later meeting, Denuto is direct and straight-forward with Kerrigan when he tells him, "I'm not qualified. . . . I'm not in the big-time. It's over my head."

![]() Denuto finally gives in to Darryl Kerrigan's persistent efforts, and

against his better judgment, takes on the case. We are reminded

of the unsuccessful efforts by the colleagues and family of Ann Talbot,

the lawyer in the "Music Box," to persuade her not to represent

her father who has been charged with fraud in gaining entry into the

United States. Ann Talbot managed to weather the storm created by

the trial and the knowledge she gained of her father's war crimes,

but we know she should have declined to represent her father, but there are all kinds of shoulds in life which we feel compelled

to ignore.

Denuto finally gives in to Darryl Kerrigan's persistent efforts, and

against his better judgment, takes on the case. We are reminded

of the unsuccessful efforts by the colleagues and family of Ann Talbot,

the lawyer in the "Music Box," to persuade her not to represent

her father who has been charged with fraud in gaining entry into the

United States. Ann Talbot managed to weather the storm created by

the trial and the knowledge she gained of her father's war crimes,

but we know she should have declined to represent her father, but there are all kinds of shoulds in life which we feel compelled

to ignore.

Dennis Denuto knows, as does the viewer, that his representation of Darryl Kerrigan is going to come to no good end, bBut doing what he should do is not all that easy. To say no to Kerrigan means Kerrigan will not have a lawyer, and his case will be lost because there is no one to help him pursue it. From this perspective, Denuto's decision to represent Kerrigan is not so much that of a stupid man who doesn't know his limits, but rather a compassionate man who does.

Denuto's humiliation when the Kerrigan matter is first heard by judges is both humorous, sad, and instructive. It's humorous because he argues the case with the same skill that he tries to fix his office Xerox machine. It's hard to imagine a lawyer who doesn't know enough about the law of a case he is arguing to be able to point to the specific law and legal language that will be applicable in the case. We might pause here to reflect on how the ignorance of a lawyer, Dennis Denuto in "The Castle," and the unskilled lawyer in "My Cousin Vinny," provide the grounds for humor. While Denuto's argument that it's "the vibes" of the Australian Constitution that require the court to rule in his client's favor seems simply ridiculous, there may be, even in this humorous situation, a broader jurisprudential point to be considered. Is the Constitution to be read like a statute? Literally? I hear suggestions quite frequently from politicians that this is exactly how we are to read the Constitution. Dennis Denuto may have made a fool of himself, but I'm not sure that in his talking about constitutional vibes he wasn't on as firm a jurisprudential ground as those who call for a literal interpretation of the Constitution and demand that judges apply rather than make law. Foolishness in high places abounds when it comes to talking about the Constitution. Dennis Denuto, in his botched argument for Darryl Kerrigan may, ultimately, be less the fool than we would have him be.

![]() The Political Film Society review refers to "The Castle" as a satire. What is satirized in this film?

The Political Film Society review refers to "The Castle" as a satire. What is satirized in this film?

![]() The affection we feel for Darryl Kerrigan extends to the well-meaning, if sometimes incompetent lawyer, Dennis Denuto, and to Lawrence Hammill, the distinguished Queen's Counsel who meets Kerrigan quite by chance and decides to take his case to the High Court of Australia. How does Hammill, a rather stand-offish and stately lawyer, gain our affection? [Report on the Legal Profession: Queen's Counsel]

The affection we feel for Darryl Kerrigan extends to the well-meaning, if sometimes incompetent lawyer, Dennis Denuto, and to Lawrence Hammill, the distinguished Queen's Counsel who meets Kerrigan quite by chance and decides to take his case to the High Court of Australia. How does Hammill, a rather stand-offish and stately lawyer, gain our affection? [Report on the Legal Profession: Queen's Counsel]

Notes

![]()

![]() On Comedy: I found the following observation by James Bonnet in Stealing Fire From the Gods: A Dynamic New Story Model for Writers and Filmmakers 200-201 (Studio City, California: Michael Wiese Productions, 1999) might be put to use to understanding our reading of "The Castle":

On Comedy: I found the following observation by James Bonnet in Stealing Fire From the Gods: A Dynamic New Story Model for Writers and Filmmakers 200-201 (Studio City, California: Michael Wiese Productions, 1999) might be put to use to understanding our reading of "The Castle":

If you are creating a tragedy or a romance, you are exaggerating the nobility of the characters and putting the audience in touch with their true potential. You are giving them a taste of who they really are. If you're creating a comedy, the basic situation will still be real, but you are isolating and exaggerating the foibles and flaws people have, the frequency with which errors occur, and the irony experienced by your characters. Woody Allen makes people laugh by exaggerating his own hypochondria and neurosis. . . . The more laughter you can provoke, the closer you are to getting to the truth. Even serious plays like Hamlet have, or should have, a great deal of humor. A story without humor is not about human beings.

There might be something in Bonnet's comment on comedy and life that lawyers might want to keep in mind. We are engaged in the most serious kind of work, but we would do well to remember that work that permits no humor diminishes us as human beings.

![]() Australian Cases Cited: Mabo

v. Queensland :: Mabo

v. Queensland [2] :: Tasmanian

Dam Case

Australian Cases Cited: Mabo

v. Queensland :: Mabo

v. Queensland [2] :: Tasmanian

Dam Case

![]() Related U.S. Cases: The use of eminent

domain to take private property for "public use": Kelo

v. City of New London, Connecticut, et. al., 545 U.S. 302 (2005) [on-line

PDF files of the opinion] [Wikipedia]

Related U.S. Cases: The use of eminent

domain to take private property for "public use": Kelo

v. City of New London, Connecticut, et. al., 545 U.S. 302 (2005) [on-line

PDF files of the opinion] [Wikipedia]

![]() "It's the vibes" in U.S. jurisprudence: Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965) [on line text]

"It's the vibes" in U.S. jurisprudence: Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965) [on line text]

![]() Reviews: A

Man's Home is His Castle :: Michae;

D's DVD Page :: Newsweek

:: David

Stratton :: Sacramento

News :: Time

Out-London :: Reeling

Reviews :: TheBeautifulMovie.com

Reviews: A

Man's Home is His Castle :: Michae;

D's DVD Page :: Newsweek

:: David

Stratton :: Sacramento

News :: Time

Out-London :: Reeling

Reviews :: TheBeautifulMovie.com

![]() Film Basics

Film Basics