Crime Film Documentaries

Instructor: James R. Elkins

| fall | 2018 |

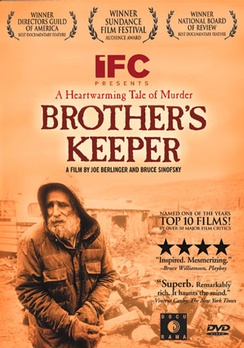

"Brother's Keeper"

(1992)

[1 hr. 45 mins.] [Film by Joe Berlinger & Bruce Sinofsky]

[currently avilable on NETFLIX]

"This acclaimed documentary explores the odd world of the four elderly Ward brothers--illiterate farmers who have lived their entire lives in a dilapidated two-room shack. When William Ward dies in the bed he shared with his brother Delbert, the police become suspicious. Citing motives ranging from sex crime to euthanasia, they arrest Delbert for murder, penetrating the isolated world that left 'the boys' forgotten eccentrics for many years." ~ Netflix

"The first feature-length effort by documentary filmmakers Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky, Brother's Keeper unfolds a strange-but-true story about a most unorthodox family. 59-year-old Delbert Ward lives with his brothers Bill, Roscoe, and Lyman on a dairy farm near the upstate New York village of Munnville. Barely able to function on an adult level, the Ward brothers keep to themselves, ignored and shunned by their neighbors. When older brother Bill dies on June 5, 1990, the authorities determine that his death was not from natural causes. Suspected of a mercy killing, Delbert is charged with second degree murder. It gradually becomes apparent that the police coerced Delbert into signing a confession, whereupon his neighbors, who previously wanted nothing whatsoever to do with the man, begin lobbying passionately for his release. It's not that they believe that he's innocent, it's simply that he is one of 'theirs.' Berlinger and Sinofsky firmly refuse to sugarcoat their subject; their glimpses of the Mann brothers and their bizarre lifestyle might be unsettling to some. In addition to its other accomplishments, Brother's Keeper also demonstrates in a non-judgmental fashion how the media can manipulate public opinion, both positively and adversely." ~ Hal Erickson, All Movie Guide

![]() Readings

(to be provided to you when we screen the film)

Readings

(to be provided to you when we screen the film)

"Best Brothers: The Delbert Ward Case," in Cyril Wecht, Cause of Death 235-259 (Onyx, 1994) [Dr. Wecht testified for the defense in the Delbert Ward murder trial] [Cyril Wecht]

Thomas M. Kemple, Litigating Illiteracy: The Media, the Law, and The People of the State of New York v. Adelbert Ward, 10 Can. J.L. & Soc. 73 1995).

![]() Film Reviews:

Roger

Ebert

Film Reviews:

Roger

Ebert ![]() Desson

Howe (Washington Post)

Desson

Howe (Washington Post) ![]() Rita

Kempley (Washington Post)

Rita

Kempley (Washington Post) ![]() Vincent

Canby (New York Times)

Vincent

Canby (New York Times) ![]() Nathan

Raban

Nathan

Raban ![]() Austin

Chronicle

Austin

Chronicle ![]() NY

Daily News

NY

Daily News ![]() Baltimore

Sun

Baltimore

Sun ![]() Dan

McComb

Dan

McComb![]() Spirituality

& Practice (review by Frederic Brussat & Mary Ann Brussat)

Spirituality

& Practice (review by Frederic Brussat & Mary Ann Brussat)

![]() Hardscrabble

(commentary by Chas S. Clifton)

Hardscrabble

(commentary by Chas S. Clifton) ![]() Rolling

Stone

Rolling

Stone ![]() New

York Times Guide to the Best 1,000 Movies Ever Made

New

York Times Guide to the Best 1,000 Movies Ever Made

![]() An

Account of the Case and the Community Involvement in It: A

Death in the Family [a series (5 parts) by Hart

Seely]

An

Account of the Case and the Community Involvement in It: A

Death in the Family [a series (5 parts) by Hart

Seely]

![]() Historical-Fiction

Novel: Jon Clinch's Kings of the Earth (Random House,

2010) is a historical-fiction novel based on the 1990 murder trial of

Delbert Ward. [Los

Angeles Times

book review]

Historical-Fiction

Novel: Jon Clinch's Kings of the Earth (Random House,

2010) is a historical-fiction novel based on the 1990 murder trial of

Delbert Ward. [Los

Angeles Times

book review]

![]() Newspaper

& Magazine Accounts: Los

Angles Times

article || A

Death's Tale Goes National || People

magazine article

Newspaper

& Magazine Accounts: Los

Angles Times

article || A

Death's Tale Goes National || People

magazine article

![]() Bibliography:

Thomas M. Kemple, Litigating Illiteracy: The Media, the Law, and

The People of the State of New York v. Adelbert Ward, 10 Can. J.L.

& Soc. 73 (1995) (Kemple is a professor of sociology at the University

of British Columbia) [this article can be found using

the HeinOnline database][The article is of minimal use for our purposes,

but does present a transcript of a comment by the neighbor, John Teeple,

that is of value, as is Kemple's drawing attention to the rural/urban

culture differences so adeptly presented in the film.]

Bibliography:

Thomas M. Kemple, Litigating Illiteracy: The Media, the Law, and

The People of the State of New York v. Adelbert Ward, 10 Can. J.L.

& Soc. 73 (1995) (Kemple is a professor of sociology at the University

of British Columbia) [this article can be found using

the HeinOnline database][The article is of minimal use for our purposes,

but does present a transcript of a comment by the neighbor, John Teeple,

that is of value, as is Kemple's drawing attention to the rural/urban

culture differences so adeptly presented in the film.]

![]() Portraying

Delbert Ward (and his brothers) to the Jury: How are you going

to describe/define/convey Delbert Ward, and his brothers, to the jury?

(How do the filmmakers portray Delbert and his brothers?)

Portraying

Delbert Ward (and his brothers) to the Jury: How are you going

to describe/define/convey Delbert Ward, and his brothers, to the jury?

(How do the filmmakers portray Delbert and his brothers?)

How do you conduct a voir dire for the selection of the jury in this case?

Do you ask for a jury visit to the ramshackle shack where the brothers live? (Should the trial court judge grant such a motion?)

Here are some terms used by viewers and in film reviews to describe the Ward brothers:

simple | different | illiterate | virtually illiterate | nearly illiterate | throw-backs in time | out of touch with modern life | recluses | outcasts | peculiar | eccentric | "harmless old coots" (Roger Ebert) | slow-witted | retarded | genial | shy and gentle souls | warm, likable people | sweet-natured | "boys" | bachelors | filthy bachelors with unkempt beards | farmers | indigent farmers | primitive dairy farmers | brothers | neighbors |

On the DVD back cover, we find the following descriptive terms: "eccentric brothers" | "eccentric farmers" | "elderly bachelors" | "uneducated hermit" (Delbert Ward)

![]() The Interrogation

and Confession of Delbert Ward

The Interrogation

and Confession of Delbert Ward

How you present Delbert Ward to the jury is going to be part and parcel of your efforts to deal with the fact that he signed a confession and the confession is going to be made part of the prosecution's case.

"Patently clear from the outset (to everyone but the police and prosecutors) is that Delbert is not a person who should be signing confessions without the benefit of counsel. One townsperson astutely observed that Delbert probably didn't know the difference between waving to someone in the street and waiving his rights." [Marjorie Baumgarten, The Austin Chronicle (January 29, 1993)]

Note: The prosecution went to considerable effort to show that Delbert Ward knowingly waived his rights to a lawyer and knowing and willingly gave the statement in which he confessed to his brother's killing. The prosecution tries to show that Delbert is not nearly so isolated or so illiterate as the defense claims. Christopher Null in a 2003, filmcritic.com review of "Brother's Keeper": "Is Delbert really as dim as he seems? After all, the guy watches Jeopardy." The prosecution attempts to show that Delbert is more savvy than he lets on, and even that he knows what it means to waive his legal rights by showing that Delbert watched "Hunter" a TV program about a detective who has, evidently, on some of the programs, criminal suspects were depicted as being given their Miranda warnings, and by watching "Matlock"— a TV program starring Andy Griffin as a lawyer.

To make a "knowing" waiver of his rights, the prosecution tries to show that Delbert Ward has a media literacy that will stand-in for his questionable reading|writing illiteracy. Can Delbert Ward read? We learn he did not have his glasses with him at the police station. The issue as to whether he can read with glasses is left unresolved in the film. [Cyril Wecht, in his account of the trial, notes that whenever Delbert was "asked to read or sign something, he would conveniently claim he didn't have his glasses on him."]["Best Brothers: The Delbert Ward Case," in Cyril Wecht, Cause of Death 235-259, at 239 (Onyx, 1994)]

There is, in the film, a struggle over "locating" Delbert's literacy/illiteracy. In this struggle, the lawyers attempt not just to describe and define Delbert Ward but to do so in a way that leads the jury to a decision as to whether he could knowing waive his rights. (Why, one might ask, wasn't the confession thrown out in a pretrial motion to suppress hearing?)

It is one thing to point to Delbert's illiteracy, still another to "prove" that he is mentally retarded. Note that a clinical psychologist who interviews Delbert and testifies at the trial gave him some tests and found that he was "mentally retarded" and has a "schizoid personality disorder." [Schizoid personality disorder–Wikipedia]

One of the few academic articles written about the trial is Thomas M. Kemple, Litigating Illiteracy: The Media, the Law, and The People of the State of New York v. Adelbert Ward, 10 Can. J.L. & Soc. 73 (1995) [The article can be found on HeinOnline.] Note the irony in the title. Kemple is, of course, referring most obviously to Delbert Ward's illiteracy and how it is being litigated in his murder trial.

The Exoneration of Ronald Kitchen [5:21 mins.] [CBS, July 28, 2009] [1:44 mins.] || Coerced Confessions, NYCLU Calls on Police to Videotape Interrogations ||| How to Get a False Confession in Ten Easy Steps [Nathan J. Gordon, director of the Academy for Scientific Investigative Training, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; author of Effective Interviewing and Interrogation Techniques]

False Confessions

False Confessions:

Causes, Consequences, and Implications [Richard A.

Leo, 37 (3) J. Am. Acad. Psychiatry Law :332 (2009)] || Police

Interrogations and Confessions [Saul Kassin] || Untrue

Confessions [Paul Cassell] |

![]() The Decision to

Charge Delbert Ward with Murder

The Decision to

Charge Delbert Ward with Murder

One of Delbert Ward's neighbors, John Teeple, comments in the film:

There's always been this antagonism between the big city and the rural areas. Y'know, if you're born in the rural area and make it good it must mean that you go to the city and make it good . . . And city people, I think, are inclined to look at country people as bumpkins, as probably not terribly bright and not awfully strongly motivated, and nothing could be further from the truth if you see the way some of these farmers work. And I suspect that the city stereotype is in the heads of the BCI and the District Attorney, and they probably don't know it; it's just part of the culture that you think of rural areas that way, you see. And I think maybe that's part of the drawing together of Munnsville behind Delbert, is that the we against them, them being the in quotes ‘City DA' trying to get poor Delbert up there on the hill." [transcribed comment of John teeple in Thomas M. Kemple, Litigating Illiteracy: The Media, the Law, and The People of the State of New York v. Adelbert Ward, 10 Can. J.L. & Soc. 73, 91 (1995)]

Thomas M. Kemple's statement of the problem goes like this:

The cultural ambiguities which seem ultimately to have determined Delbert Ward's case emerged in part from a perceptual gap in the world view of people from a certain rural area in opposition to the perceptions of them by people living in a nearby urban centre." [Thomas M. Kemple, Litigating Illiteracy: The Media, the Law, and The People of the State of New York v. Adelbert Ward, 10 Can. J.L. & Soc. 73, 90 (1995)]

The "urban centre" identified by Kemple is the Bureau of Criminal Investigation, the Medical Examiner, and the DA's office (presumably all of them working from Syracuse). What we see in the film is what Kemple describes, in passing, as "city professionals" with their "specialized tasks and functions." [91] Kemple argues "that the hyperliteracy of the bureaucratic legal profession, especially when confronted with relative or absolute illiteracy, forces us to peer into the blind spot of modern society, indeed, to sound out the zero point of contemporary culture." [97]

Kemple also makes reference to "urban and rural conceptions of justice" and to rural and urban culture. [90, 91]

Kemple hints at something important going on in this film, and obscures the point in making it:

[A]n analysis of Delbert Ward's trial constitutes a kind of test case or cultural experiment which exposes the unarticulated sacred foundations of social life—before they are usurped from the everyday world of ritual communication and common sense and subjected to the secular linguistic orders of rationalized discourse and criticism. [97]

As I work through this stark dichotomy in the film, between the professionals—the DA, police investigators, medical examiner (or what we might call the "suits")—and the Wards and their world, I am reminded of some interesting literary references. First, Tolstoy's "The Death of Ivan Ilych" where we find a legal bureaucrat who distances himself from the common people who appear before him in his official capacity:

[A]s an examining magistrate, Ivan Ilych felt that everyone without exception, even the most important and self-satisfied, was in his power, and that he need only write a few words on a sheet of paper with a certain heading, and this or that important, self-satisfied person would be brought before him in the role of an accused person or a witness, and if he did not choose to allow him to sit down, would have to stand before him and answer his questions. Ivan Ilych never abused his power; he tried on the contrary to soften its expression, but the consciousness of it and the possibility of softening its effect, supplied the chief interest and attraction of his office. In his work itself, especially in his examinations, he very soon acquired a method of eliminating all considerations irrelevant to the legal aspect of the case, and reducing even the most complicated case to a form in which it would be presented on paper only in its externals, completely excluding his personal opinion of the matter, while above all observing every prescribed formality."

Ilych lived had a "separate fenced-off world of official duties . . . ."

He got up at nine, drank his coffee, read the paper, and then put on his undress uniform and went to the law courts. There the harness in which he worked had already been stretched to fit him and he donned it without a hitch: petitioners, inquiries at the chancery, the chancery itself, and the sittings public and administrative. In all this the thing was to exclude everything fresh and vital, which always disturbs the regular course of official business, and to admit only official relations with people, and then only on official grounds. A man would come, for instance, wanting some information. Ivan Ilych, as one in whose sphere the matter did not lie, would have nothing to do with him: but if the man had some business with him in his official capacity, something that could be expressed on officially stamped paper, he would do everything, positively everything he could within the limits of such relations, and in doing so would maintain the semblance of friendly human relations, that is, would observe the courtesies of life. As soon as the official relations ended, so did everything else. Ivan Ilych possessed this capacity to separate his real life from the official side of affairs and not mix the two, in the highest degree, and by long practice and natural aptitude had brought it to such a pitch that sometimes, in the manner of a virtuoso, he would even allow himself to let the human and official relations mingle. He let himself do this just because he felt that he could at any time he chose resume the strictly official attitude again and drop the human relation. And he did it all easily, pleasantly, correctly, and even artistically.

Thinking about Delbert Ward, I'm reminded also of the isolated and reclusive, Boo Radley, who becomes the object of fascination of Jem and Scout Finch in Harper Lee's To Kill a Mockingbird. The locked-away outcast Boo Radley befriends Scout and Jem and when Bob Ewell attacks the children on their way home from a school program, Boo saves their lives by killing Bob Ewell. Knowing the reclusive Boo Radley as both Sheriff Tate and Atticus Finch do, persuades Atticus not to make Boo Radley's involvement public as it would, the sheriff argues, destroy the man. The sheriff finally brings Atticus, reluctantly, to agree that it it would be a great wrong to push Boo Radley into the limelight by having him tried for killing Bob Ewell (assuming as we do that Boo Radley would have a viable "defense of others" claim). Atticus has told the children that it's a sin to kill a mockingbird, and Scout recalls this, as a reason to protect Boo Radley from the harsh light of public exposure. Delbert Ward, in this case, is himself something of a mockingbird.

![]() On the People

vs. the Law

On the People

vs. the Law

The Legal Profession [Lawyers for One America]

![]() Medical Examiner:

Autopsy

Medical Examiner:

Autopsy

Petechia [Wikipedia]

Susan F. Ely & Charles S. Hiersch, Asphyxial Deaths and Petechiae: A Review, 45 J. Forensic Sci. 1274 (2000) [online text]

![]() Joe Berlinger,

the Filmmaker: Joe

Berlinger, "Brother’s Keeper” to “Intent to Destroy” [podcast:

43:22 mins.]

Joe Berlinger,

the Filmmaker: Joe

Berlinger, "Brother’s Keeper” to “Intent to Destroy” [podcast:

43:22 mins.]