James R. Elkins

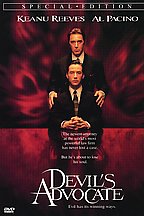

"A Devil's Advocate"

(1997)

Film Basics

Screenplay by Jonathan Lemkin & Tony Gilroy

[based on the novel by Andrew Neiderman][1997]

![]()

"The Devil’s Advocate" (1997) is a film unlikely to find favor with legal film critics. The lawyer protagonist in the film, Kevin Lomax (Keanu Reeves) is found by legal commentators to be both ludicrous and still, by some means, a threat to the legal profession. These are the film critics who cannot bear the thought that a lawyer might be associated with the work of the Devil.

Kevin Lomax’s threat to right thinking about the legal profession is made more serious by the fact that he is young, handsome, married to a beautiful wife, and awfully good at his work. Moreover, Kevin Lomax seems to have a special talent, a way of understanding jurors that makes it possible for him to win what would appear to be unwinnable cases. Kevin Lomax is a lawyer to be envied, so talented that we wonder just what he might be capable of achieving. We then learn—as if we did not know already—that Kevin Lomax can be lured, by the promise of his talent, the great reach of his ambition, and the ability of others to see his unfulfilled needs, to cross the line (indeed, several lines) for which we know he must pay a price.

What we find in "The Devil’s Advocate" is that Kevin Lomax, by the nature of his work, has begun to represent clients that are basically no-good, clients who are, for those who still believe in evil, exemplars of evil. Further, he allows his great talent to be used on behalf of these questionable clients. Lawyers like Kevin Lomax deal with real badness (confusion, poor judgment, weakness of character, as well as social and culturally sanctioned excess); they see, talk, touch, and litigate this badness. And then, in getting up close to real badness and the fallen world of their clients, they are in turn put in danger by it. Should we be surprised that lawyers like Kevin Lomax cross the line, and sometimes, metaphorically, take sides with the Devil?

It is Kevin Lomax’s crossing-over, which we are allowed to see and which we see in lawyer films generally, that threatens the stability of our settled views as lawyers and legal film critics. To the great horror of legal film commentators, viewers find this crossing-over entertaining as it resonates with what the public believes to be truth (God forbid) about lawyers—that they can be bought and their advocacy put to use by the Devil. Since Hollywood lawyer films need neither to conform to our conventional thinking about lawyers and the legal profession, nor present lawyers in the celebratory way we most want to be seen, we are spared, in films, the insider’s spin. The fear of lawyers and legal critics who warn against a Kevin Lomax story is that we might begin to take it seriously, that the public might begin to think that lawyers do the Devil’s work (still more threatening since the Devil in The Devil’s Advocate, John Milton—Al Pacino—turns out to be an entertaining, intellectual, and philosophically astute character).

The film critics want to tell us, as they tell themselves, that lawyers simply cannot be thought of in the way Kevin Lomax allows us to see them. To protect the good name of lawyers, we need someone to ridicule Lomax as unrepresentative of the legal profession. Since we cannot be the enemy, Lomax must be a character invented by Hollywood to further torment and threaten the (good) work of real world lawyers.

That lawyers, in films and beyond films, traffic in the broken, the shady, the false, the fraudulent, and the criminal, while making a good living doing it, is not a well-kept secret. That we do this underground work, and hold so sanctimoniously to the virtue and ethics of a profession, suggests an emperor with no clothes.

Working with lawyer films, and knowing something about real world lawyers, we are left with a simple question: Does a compact between a lawyer and the Devil make any sense, any experienced (real world) sense, any cinematic sense? We know it has made for some telling moments in The Devil’s Advocate (and did so in a film which at times was so over-the-top, excessive, and downright weird that it sometimes threatened the coherence of the film). Kevin Lomax’s compact with the Devil made for high drama, and at times compelling drama, even though it may not have resulted in a great film. Is not the compact with the Devil an imaginative context for revisiting the devilish play of good and evil, the good and evil we find in the work of zealous lawyers? Where do the good lawyering talents of Kevin Lomax (and real-world lawyers) end and the work of the Devil begin?

In contrast to the legal film police, I think we should appreciate the educational value of lawyer-film villains who are portrayed with all their foibles and warts, lawyers so unethical we gasp at their audacity. Only when confronted with the most profound villainy, can we celebrate raw virtue (most often in the same film, the same drama, and in some instances, the same character who has so vividly and compellingly portrayed the negative elements of our character and our profession).

Kevin Lomax, seduced by his own talent and by the lure of a big city law practice, shows us how ordinary it is for talented lawyers to want to push themselves, their talents, their skills, and their lawyering, as far as their endowments can take them. We (viewers) know that pushing on in this way cannot be done without danger. And if there is danger to be risked, let it be Kevin Lomax who takes the far-out trip with the Devil. The film-viewer wants to say to Lomax—“Boy, you’ve got a talent that’s a pretty thing to see, now you be careful you don’t let this powerful thing you’ve got lead you astray.” (Ride the tiger, get eaten by the tiger.) Can Kevin Lomax not see that his powerful talents, used indiscriminately and unreflectively, undermine everything that he believes he is? Is it anti-lawyer, or a detrimental negative portrayal of a lawyer, to particularize and give full character to the presence of a talent so powerful that it leads one to sign on for the Devil’s work?

[Adapted from, James R. Elkins, Reading/ Teaching Lawyer Films, 28 Vt. L. Rev. 814 (2004)]

Note: For a brief account of the TV drama, Ally McBeal–which is, in the oddest of ways, a law/legal/lawyer drama–taken all too seriously, and without a hint that Alley McBeal might be seen/read/understood as comedy or satire, see David M. Spitz, Heroes or Villains? Moral Struggles vs. Ethical Dilemmas: An Examination of Dramatic Portrayals of Lawyers and the Legal Profession in Popular Culture, 24 Nova L. Rev. 725, 734 (2000) (describing Ally McBeal as absurd, unrealistic, and preposterous and in so being gives rise to “embarrassing damage to the profession,” damage which “likely supersedes the intended comic relief.” Id. at 736). Whether the legal profession may have been damaged in any way by the lawyer antics in Alley McBeal is, of course, pure speculation. And the relationship between the damage to the legal profession induced by satire, comedy, and ridicule found in the representation of lawyers in film in contrast to the damage that real lawyers inflict upon the legal profession is clearly unknown and unmeasured. What we do know is that many lawyers, and those who speak for them in legal scholarly circles, seeing themselves represented in this comedic mode, tend to be downright defensive.