James R. Elkins

"To Kill a Mockingbird"

(1962)

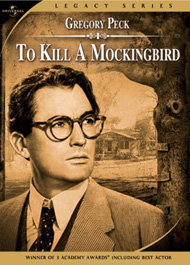

![]() The novel,

To Kill a Mockingbird, won the Pulitzer Prize when it

was published in 1960 and the film, with screen adaptation of the novel by Horton Foote, staring Gregory Peck and Robert Duvall in a debut film role as the Finch's neighbor, Boo Radley, received eight Academy Award nominations and won the Academy Award for

Best Picture of the Year.

The novel,

To Kill a Mockingbird, won the Pulitzer Prize when it

was published in 1960 and the film, with screen adaptation of the novel by Horton Foote, staring Gregory Peck and Robert Duvall in a debut film role as the Finch's neighbor, Boo Radley, received eight Academy Award nominations and won the Academy Award for

Best Picture of the Year.

To Kill a Mockingbird is undoubtedly the most widely read and memorable book about a lawyer in American literature. Atticus Finch has become something of a patron saint for many lawyers. Atticus Finch is, quite simply, one of the most esteemed heroes in fiction. Rennard Strickland, a long-time student of lawyer films, says that "Atticus Finch—of all screen lawyers [is] the most idealized and probably the most idolized. To Kill a Mockingbird , Harper Lee's Lincolnesque version of her father, as portrayed by Gregory Peck, has become our cinematic standard of the profession at its very best." [Rennard Strickland, "The Hollywood Mouthpiece: An Illustrated Journey Through the Courtrooms and Back-Alleys of Screen Justice," in David L. Gunn (ed.), The Lawyer and Popular Culture: Proceedings of a Conference 49-59, 51 (Littleton, Colorado: Fred B. Rothman & Co., 1993)]

![]() "To Kill a Mockingbird" is an interesting and powerful film,

but no film can do full justice to an imaginatively conceived novel with

finely developed characters. And so it is, with "To Kill a Mockingbird."

In reading a film adapted from a worthwhile novel, it makes good sense

to read the novel.

"To Kill a Mockingbird" is an interesting and powerful film,

but no film can do full justice to an imaginatively conceived novel with

finely developed characters. And so it is, with "To Kill a Mockingbird."

In reading a film adapted from a worthwhile novel, it makes good sense

to read the novel.

![]() Terry Rossio, in a screenwriting column entitled "The Audience

is Listening," argues that "every movie has one main relationship at its

core. One relationship that is the heart of your movie, one that defines

your movie." He goes on to point out that the relationship "[c]ould be

a romance. Could be a buddy movie. Could be a detective playing cat-and-mouse

with a killer. Could be a father-son family drama. But there will always

be a central relationship going on up there on screen, and the shape of

that relationship will help form the shape of your story."

While Rossio may be wrong to focus on the singular nature of the

relationship found in a film, the idea of trying to locate the relationships

embedded in the story seems sensible.

Terry Rossio, in a screenwriting column entitled "The Audience

is Listening," argues that "every movie has one main relationship at its

core. One relationship that is the heart of your movie, one that defines

your movie." He goes on to point out that the relationship "[c]ould be

a romance. Could be a buddy movie. Could be a detective playing cat-and-mouse

with a killer. Could be a father-son family drama. But there will always

be a central relationship going on up there on screen, and the shape of

that relationship will help form the shape of your story."

While Rossio may be wrong to focus on the singular nature of the

relationship found in a film, the idea of trying to locate the relationships

embedded in the story seems sensible.

What are the central relationships in "To Kill a Mockingbird"? How do these relationships define the film? the characters? the conflict confronted by the characters? the growth of the characters?

![]() There is another relationship that is central to

our understanding of a film—that of the viewer with the characters,

primarily the film's protagonists and other central characters. How does

your identification (or failure to identity with) the lawyer(s) in these

films help or hinder your understanding of the film?

There is another relationship that is central to

our understanding of a film—that of the viewer with the characters,

primarily the film's protagonists and other central characters. How does

your identification (or failure to identity with) the lawyer(s) in these

films help or hinder your understanding of the film?

Rossio, in "The Audience is Listening," points out that "the protagonist allows the audience access into the story." How does "To Kill a Mockingbird" complicate Rossio's point?

|

How is our hope for the characters in "To Kill a Mockingbird" evoked? |

|

Rossio makes an interesting point about the power of the filmmaker to "touch the audience." He sees in our willing identification with the film characters a corresponding power of the filmmaker to use these characters and the changes brought about in their lives to "touch" the viewer. And it is this power that gives rise to the claim that movies, made for a mass audience, and attended for entertainment, can have a direct influence on the way we try to live.

|

|

|

![]() Lawyer films, inevitably, explore the place of law in

society. Law is also portrayed as a kind of world apart, with its

own culture and actors, its own way of doing things. The relationship

of law and society is not limited to lawyer films. It features prominently

in other film genres as well, in particular Westerns, detective stories,

and police dramas. In their dealings with the law/society relationship,

what sets lawyers apart from cowboys, detectives, and policemen?

Lawyer films, inevitably, explore the place of law in

society. Law is also portrayed as a kind of world apart, with its

own culture and actors, its own way of doing things. The relationship

of law and society is not limited to lawyer films. It features prominently

in other film genres as well, in particular Westerns, detective stories,

and police dramas. In their dealings with the law/society relationship,

what sets lawyers apart from cowboys, detectives, and policemen?

![]() Conflict plays a central role in film drama. Robert McKee

says, "the principle of antagonism is the most important and least understood

precept in story design." McKee presents the principle in its most basic

form: "A protagonist and his story can only be as intellectually fascinating

and emotionally compelling as the forces of antagonism make them."

[Robert McKee, Story: Substance, Structure, Style,

and the Principles of Screenwriting 317 (1998) (emphasis in original].

The forces of antagonism can be external or internal to the central character.

What forces of antagonism play out in the lives of the central characters

in "To Kill a Mockingbird"?

Conflict plays a central role in film drama. Robert McKee

says, "the principle of antagonism is the most important and least understood

precept in story design." McKee presents the principle in its most basic

form: "A protagonist and his story can only be as intellectually fascinating

and emotionally compelling as the forces of antagonism make them."

[Robert McKee, Story: Substance, Structure, Style,

and the Principles of Screenwriting 317 (1998) (emphasis in original].

The forces of antagonism can be external or internal to the central character.

What forces of antagonism play out in the lives of the central characters

in "To Kill a Mockingbird"?

McKee argues that "[t]he more powerful and complex the forces of antagonism opposing the [protagonist] character, the more likely we are to have a protagonist who is "fully realized, multidimensional, and deeply empathetic. . . ." [Id.] Bob Ewell, who has brought on the prosecution of an innocent, Tom Robinson, is neither powerful or complex. Mr. Gilmer, the prosecutor in the Tom Robinson case, plays a minor (stereotyped) role. How do the forces of antagonism in "To Kill a Mockingbird" take on complexity?

![]() How is the ordinary world of the Finch household presented

in this film?

How is the ordinary world of the Finch household presented

in this film?

Here is the passage from the novel:

Maycomb was an old town, but it was a tired old town when I first knew it. In rainy weather the streets turned to red slop; grass grew on the sidewalks, the courthouse sagged in the square. Somehow, it was hotter then: a black dog suffered on a summer's day; bony mules hitched to Hoover carts flicked flies in the sweltering shade of the live oaks on the square. Men's stiff collars wilted by nine in the morning. Ladies bathed before noon, after their three-o'clock naps, and by nightfall were like soft teacakes with frostings of sweat and sweet talcum.

People moved slowly then. They ambled across the square, shuffled in and out of the stores around it, took their time about everything. A day was twenty-four hours long but seemed longer. There was no hurry, for there was nowhere to go, nothing to buy and no money to buy it with, nothing to see outside the boundaries of Maycomb County. [Harper Lee, To Kill a Mockingbird 11 (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1960)]

How is the ordinary world portrayed in this film threatened?

![]() In "Adam's Rib" (1949) we found Amanda Bonner portrayed as

a strong, assertive, accomplished woman lawyer (a portrayal notable given

the time when the film was made). Does the exploration of racial prejudice

in a major (award winning) Hollywood film in 1962 present another occasion

in which film becomes the medium for social commentary?

In "Adam's Rib" (1949) we found Amanda Bonner portrayed as

a strong, assertive, accomplished woman lawyer (a portrayal notable given

the time when the film was made). Does the exploration of racial prejudice

in a major (award winning) Hollywood film in 1962 present another occasion

in which film becomes the medium for social commentary?

![]() Bob Ewell, in the most sneering tone, asks Atticus Finch,

"What kind of man are you?" We might want to ask that question ourselves.

Bob Ewell, in the most sneering tone, asks Atticus Finch,

"What kind of man are you?" We might want to ask that question ourselves.

![]() What kind of world does "To Kill a Mockingbird" portray in

its representation of the Finchs, Radleys, Cunninghams, Ewells, and Ms.

Maudie and Ms. Stephanie?

What kind of world does "To Kill a Mockingbird" portray in

its representation of the Finchs, Radleys, Cunninghams, Ewells, and Ms.

Maudie and Ms. Stephanie?

![]() Of what symbolic significance is: i) Jem's efforts to see

inside the Radley house and get a look at Boo Radley; (ii) Dill's peering

into the courtroom trying to watch Tom Robinson's arraignment; (iii) Scout

and Jem's sneaking into the courtroom and looking down on the courtroom

action as Tom Robinson is found guilty; (iv) Bob Ewell's looking into

the car window at Scout and Jem when Atticus visits Helen Robinson's house;

(v) Scout, still clad in her ham costume, trying to see who is attaching

her and Jem?

Of what symbolic significance is: i) Jem's efforts to see

inside the Radley house and get a look at Boo Radley; (ii) Dill's peering

into the courtroom trying to watch Tom Robinson's arraignment; (iii) Scout

and Jem's sneaking into the courtroom and looking down on the courtroom

action as Tom Robinson is found guilty; (iv) Bob Ewell's looking into

the car window at Scout and Jem when Atticus visits Helen Robinson's house;

(v) Scout, still clad in her ham costume, trying to see who is attaching

her and Jem?

Is there any special symbolic significance in the mad dog staggering down a residential street in Maycomb? In Atticus's being implored by the sheriff to shoot the mad dog?

![]() Atticus tells the jury in his closing argument: "This case

should never of come to trial." If you agree with Atticus's assessment,

what does this tell you about the prosecutor? [For

a different perspective on the Southern prosecutor, see Pete Dexter, Paris

Trout (New York: Penguin Books, 1989)]

Atticus tells the jury in his closing argument: "This case

should never of come to trial." If you agree with Atticus's assessment,

what does this tell you about the prosecutor? [For

a different perspective on the Southern prosecutor, see Pete Dexter, Paris

Trout (New York: Penguin Books, 1989)]

![]() As the film ends, Sheriff

Tate devises a story designed to protect Boo Radley and avoid dragging

him into the "limelight" which he says would be "sin." Scout says the

sheriff was right and that "[i]t would sorta be like shooting a mockingbird

wouldn't it?" What lesson are we supposed to draw from the sheriff's story

and the fact that it is less than truthful?

As the film ends, Sheriff

Tate devises a story designed to protect Boo Radley and avoid dragging

him into the "limelight" which he says would be "sin." Scout says the

sheriff was right and that "[i]t would sorta be like shooting a mockingbird

wouldn't it?" What lesson are we supposed to draw from the sheriff's story

and the fact that it is less than truthful?

How is the sheriff's story to be juxtaposed to the false

story told by the Ewells and the false story carried in the hearts and

minds of the townspeople who served on the jury that convicted Tom Robinson?

How are we to distinguish between false stories?

![]() Notes

Notes ![]()

![]() Film Bibliography

Film Bibliography

John Jay Osborn, Jr., Atticus Finch—The End of Honor: A Discussion of To Kill a Mockingbird, 30 University of San Francisco Law Review 1139 (1996)

Michael Asimow, When Lawyers Were Heroes, 30 University of San Francisco Law Review 1131 (1996)

Cramer R. Cauthen and Donald G. Alpin, The Gift Refused: The Southern Lawyer in To Kill a Mockingbird, The Client, and Cape Fear, 19 Studies in Popular Culture 257-75 (1996)

Taunya Lovell Banks, "To Kill a Mockingbird (1962): Lawyering in an Unjust Society," in Rennard Strickland, Teree E. Foster & Taunya Lovell Banks (eds.), Screening Justice—The Cinema of Law: Significant Films of Law, Order and Social Justice 239-252 (Buffalo, New York: William S. Hein & Company, 2006)

"Lawyers as Heroes" (To Kill a Mockingbird), in Michael Asimow & Shannon Mader, Law and Popular Culture: A Course Book 17-29 (New York: Peter Lang, 2004)

Film Basics

Trailer--American Film Institute

![]() Reviews: [Tom

Dirks] [DVD

Verdict] [DVD

Savant Review]

Reviews: [Tom

Dirks] [DVD

Verdict] [DVD

Savant Review]

![]() American Film Institute|Commentary|Videos

American Film Institute|Commentary|Videos

Gabriel

Byrne ![]() Amy

Madigan

Amy

Madigan ![]() James

Woods

James

Woods ![]() Nathan

Lane

Nathan

Lane

![]() Notable Scenes

Notable Scenes

Atticus Finch's Closing Argument

Atticus Finch Walks Out of Ccourt after Tom Robinson is Found Guilty

![]() Harper Lee & To Kill a Mockingbird

Harper Lee & To Kill a Mockingbird

Harper Lee's Only Recorded Interview about "To Kill A Mockingbird"

Remembering the Life and Legacy of Harper Lee

Was Harper Lee Tricked Into Releasing "Go Set a Watchman"?

![]() Producer—Alan J. Pakula: Alan J. Pakula, the

producer of "To Kill a Mockingbird" went on to direct such notable

films as "Klute," "All the President's Men," and "Sophie's

Choice."

Producer—Alan J. Pakula: Alan J. Pakula, the

producer of "To Kill a Mockingbird" went on to direct such notable

films as "Klute," "All the President's Men," and "Sophie's

Choice."

![]() Screen Adaptation by Horton Foote:

Screen Adaptation by Horton Foote:

Filmography

Internet Movie Database

Footnote: Horton Foote's son, Walter Foote, is a lawyer and an author of screen plays. [Comment of Horton Foote to Tom Sime & Jane Sumner, The Dallas Morning News, July 6, 1999]

![]() Robert Duvall—in a film debut as Arthur (Boo) Radley: Robert Duvall has played in other lawyer films including: "A Civil Action" (1999)" and

"The Gingerbread Man" (1998)

Robert Duvall—in a film debut as Arthur (Boo) Radley: Robert Duvall has played in other lawyer films including: "A Civil Action" (1999)" and

"The Gingerbread Man" (1998)

![]() Recommended Reading: Thomas Shaffer, The Moral Theology

of Atticus Finch, 42 U. Pitts. L. Rev. 181 (1981)

Recommended Reading: Thomas Shaffer, The Moral Theology

of Atticus Finch, 42 U. Pitts. L. Rev. 181 (1981)

![]() On the Novel From Which the Film Was Adapted: Symposium: To Kill

a Mockingbird , 45 Ala. L. Rev. 389-584 (1994); Claudia Johnson,

The Secrets of Men's Hearts: Codes and Law in Harper Lee's To Kill

a Mockingbird , 19 Stud. Am. Fiction 129 (1991); Claudia Durst Johnson,

To Kill a Mockingbird: Threatening Boundaries (Twayne Publications,

1995); Claudia Durst Johnson, Understanding To Kill a Mockingbird

(Greenwood Publishing, 1994)

On the Novel From Which the Film Was Adapted: Symposium: To Kill

a Mockingbird , 45 Ala. L. Rev. 389-584 (1994); Claudia Johnson,

The Secrets of Men's Hearts: Codes and Law in Harper Lee's To Kill

a Mockingbird , 19 Stud. Am. Fiction 129 (1991); Claudia Durst Johnson,

To Kill a Mockingbird: Threatening Boundaries (Twayne Publications,

1995); Claudia Durst Johnson, Understanding To Kill a Mockingbird

(Greenwood Publishing, 1994)

The novel, first published in 1960, was republished in a new hardcover edition in 1995. The sales of To Kill A Mockingbird are estimated 12 to 30 million copies sold to date. [See Timothy Huff, Influences on Harper Lee: An Introduction to the Symposium, 45 Ala. L. Rev. 389, 401 n.75 (1994); Bryan K. Fair, Using Parrots to Kill Mockingbirds: Yet Another Racial Prosecution and Wrongful Conviction in Maycomb, 45 Ala. L. Rev. 403, 404 n.9 (1994)]

![]() On Harper Lee, the author of the novel: Charles J.

Shields, Mockingbird: A Portrait of Harper Lee (Henry Holt and

Company, 2006)

On Harper Lee, the author of the novel: Charles J.

Shields, Mockingbird: A Portrait of Harper Lee (Henry Holt and

Company, 2006)

![]() Triple Feature: For an interesting contrast in Southern

lawyer film protagonists, you might watch, along with "To Kill a

Mockingbird," two other, Southern films: "Paris Trout"

(1991) [Instructor's Notes]

and "A Time to Kill" (1996).

Triple Feature: For an interesting contrast in Southern

lawyer film protagonists, you might watch, along with "To Kill a

Mockingbird," two other, Southern films: "Paris Trout"

(1991) [Instructor's Notes]

and "A Time to Kill" (1996).