|

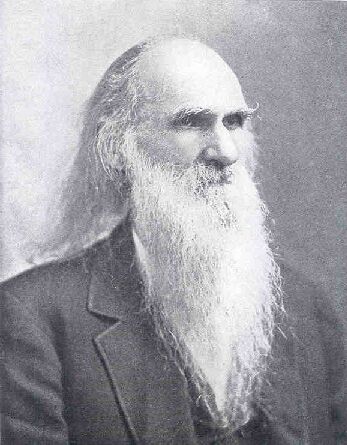

Logan E. Bleckley, Former Chief Justice of the

If a man conversant with the history both of jurisprudence and of statesmanship in the South should be asked suddenly to name the salient quality which has heretofore distinguished the masters of these two high crafts in the State of Georgia, for example, he would probably answer, unhesitatingly, eloquence. But give him time to reflect upon the eminent achievement, the public services and enduring worth of such men as Berrien, Stephens, Hill, the Cobbs, the Lumpkins and this gray-haired youngest brother of the group, Logan E. Bleckley, would he not rather change his answer to Wisdom? Nor would he mean wisdom in any restricted sense; rather that quality essential to greatness of life, wisdom, which can spring only from integrity of intellect and heart wedded to the widest, sanest knowledge. Judge Bleckley has himself said, in one of those thoughtful essays deserving to live among the choice letters of today, that "to be wise, we must discern truth and love duty. To know is not enough; to feel is not enough; we must both know aright and feel aright, and from this right knowledge and right feeling, we must send forth a life stream of right conduct." Fairly has the life of the great jurist exemplified his own simple but majestic conception of wisdom. The main facts in his career may be summed up briefly: He was born on July 3, 1827: so, while his intellectual powers are still undimmed and his physical vigor remarkable, he is already more than half a dozen years past the three-score-and-ten terminal. This enduring vigor of body and mind will doubtless be attributed by many to his being mountain-born. For a mountaineer of mountaineers is our great judge. Born on the hill-tops, as his sires before him, he has always found his dearest happiness there. His unfailing delight has been, whenever the holiday times came, the breathing-spaces in his busy career, to slip away from crowded thoroughfares and back to the mountain calms, the shades and streams and high, pure air that had made his boyhood's joy, and still stood for strength and peace in his life. His lonely little lodge on Screamer Mountain, an isolated peak of the Blue Ridge, has been, in his busiest years, a veritable paradise to him: while next has ranked in his affections the pleasant cottage in Clarksville, a hill-top village in North Georgia. In telling all this I have told, probably, the secret of Judge Bleckley's long-enduring vitalism both of physique and intellect. It was early in the mountain boy's life that he chose law as his mistress; and in the first flush of youth he was admitted to the bar. But practice came slowly; for he had opened his office in a little country town in the section of North Georgia where he was born. The location was obscure, shut in by mountains, and wholly unfavorable to professional success. Yet he had not at that time the money requisite for purchasing a library and removing to a more advantageous point. Consequently, the day was not long in arriving when the young barrister must find, temporarily, a more lucrative occupation. A clerkship in a transportation office was opportunely

offered to him, a position which he accepted and held for three

years, only giving it up when Governor Towns appointed him one of

the secretaries of the executive department. The latter place he

filled but wooing him back to her with a call which he could never

disregard. Therefore, in 1852, being then twenty-five years of age,

he opened a law office in Atlanta, where, from the first, his success

was no matter of doubt. "The office to which I aspired," said he, "was that of Solicitor-General of the Coweta circuit, which, as then constituted, embraced eight counties, and included the city of Atlanta. The office was believed and reputed to be the best-paying office in the State, and so was an object of desire by nine other gentlemen as well as myself. Three of these were so badly beaten in the race that I have forgotten their names." This election was by the Legislature on joint ballot

of the two houses, and it suffices to say that, after several ballots,

young Bleckley was chosen for the position, and that he served out

his four years' term as Solicitor-General with such distinction

that forever thereafter office and high dignity have sought him.

In 1864, he received the appointment of Reporter to the Supreme

Court. This he accepted, but resigned three years later to resume

his regular practice. But Judge Bleckley's great wisdom, as well as his

ability to serve, were too much needed in the constitution of the

State's judiciary for him to be permitted long to walk his peaceful

private ways. Earnestly and urgently he was summoned back to service

in 1887, when rounding his sixtieth year. This time the Governor

had appointed him Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. "My retirement to private life," he says,

"was voluntary, and I supposed and intended it to be perpetual.

Then the public duties of mere citizenship began seriously to engage

my attention. The noble ambition to know how to vote took possession

of me. I sincerely desired to qualify myself for the exercise of

the elective franchise. The money question was then, as it still

is, before the country, and I longed to understand it and see for

myself how it ought to be decided. My ignorance of it was utter

and profound. In the summer of 1895, laying aside all other business,

I devoted myself to the study of this one subject. At first, the

sole end I had in view was to qualify myself as a voter; but I soon

found out, from an examination of the standard works and other writings,

that nobody really understood the subject at bottom, and that I

was hardly less ignorant concerning it than the rest of mankind.

This fired me with zeal not only to master it, but to become its

expounder to the world. Accordingly, I began writing down in notebooks

brief notes of my reflections, meditations, and acquisitions touching

value and its measurement, and touching money and divers related

topics. This practice I have continued for five years, and am still

engaged in it. The note-books have multiplied to more than twenty,

and their contents to more than two thousand pages, and I frankly

say I have not yet qualified myself to vote intelligently on the

money question, though I believe I am almost qualified!" Yet what need to dwell upon the unfinished work of this venerable man? Whether it shall be completed by his own hands, or left to others, is with Him who orders wisely. But here stands the eminent jurist's seventy-year record, fair, finished, full: and it is such as the most exacting among us might well be proud to leave behind. To attempt, in a paper like this, to offer an adequate estimate of his achievements in judicature, or the value of his contributions to jurisprudence in the shape of notable decisions and weighty opinions from the Bench, would be utterly out of place, as well as supererogatory. The profession has already measured the worth of his work in that sphere, and has accorded to Judge Bleckley a place of distinction among the great living jurists. Allusion has been made, on another page, to his contributions to literature in the shape of finished essays, these being often fine and thoughtful dissertations, or again scintillant with humor, or replete with delicate sentiment. The Readers of The Green Bag will recall with especial delight that "Letter to Posterity" in the issue of February, 1893. But our paper would be indeed incomplete without reference to Judge Bleckley's poetry; for this many-gifted man is the author of some notable verse. Probably the most widely admired of his productions in verse is that fine poem of two stanzas which he read from the Bench, his last opinion during his first incumbency, and which will be found in 64 Georgia 452. A unique proceeding, truly, as it is a unique poem. It was on the occasion of his resigning from the justiceship after five of the hardest-worked, most trying years a man could have, and is entitled, "In the Matter of Rest." We reproduce it in full, as it deserves. "Rest for hand and brow and breast, Peace and rest! Are they the best A brother of the Bench, in a recent appreciation of Judge Bleckley, has most fittingly summed up the value of this poem: "The last stanza," he said, "should be burned into the heart of every young man. It is the essence of common sense, the conclusion of human experience, the final deduction of philosophy, and the ultimate dogma of religion." The poet's "Farewell to the Law" has also been widely quoted and admired. It was written and published on the occasion of his permanent retirement, in 1895, from the "fierce forensic war" in which he had been so long a central figure. The note of intense personal feeling in these verses gives them their strongest interest as well as value. You will dwell longest upon the lines: "For more than one full decade, with pale, My grand majestic master, vice-regent here It would indeed be a pleasure to give here a number of extracts from Judge Bleckley's miscellaneous verse, not only that in grave and lofty strain, but also from the many specimens in which is exhibited his marked propensity to combine humor and sentiment. But the lack of space forbids. In the latter class of his verse, we can only cite "Law Love," "Broadway," and "Cucumbers"; and in the former, "Faith," "Two Cities," and that unsurpassed sonnet upon Alexander Stephens, beginning: "Of yeoman blood, but yet of noble birth," and closing with the exalted tribute, "His state and country were to him the same, And both he served with love, and faith, and fame." One quotation must be allowed, as it gives a true insight into the character, the happy trust and love and treasure of hopefulness that are the inheritance of this gentle-hearted agnostic: "In the depths of the night * * * * No definite hope may endure, It is not our privilege to speak now of the personal character, the private walk and virtues, of this man of years and honors, to extol, as the wish impels us, the simplicity and directness which constitute the majesty of his nature, the crystal-clear truth, unwithholding benevolence and sweetness, the devotion to family and friends, which have made his life a benison. Nor may we even dwell, as we would, upon his captivating combination, in thought and speech, of Celtic wit with Anglo-Saxon force and depth of sentiment. His biographers will tell, adequately, we trust, of all these qualities. For him, the shadows are lengthening fast. But cheerful

and undaunted he looks out upon them, finding still a daily happiness

in his daily allotment. The respect and gratitude of the public

he served, the admiration of the profession he ennobled by his brotherhood

in it, the untarnished love and trust of all who were ever near

to him,—all these followed him when he left active life, to

return to his mountain calms; and they will follow him still when

he passes to the great, golden calms of the Beyond.

|