|

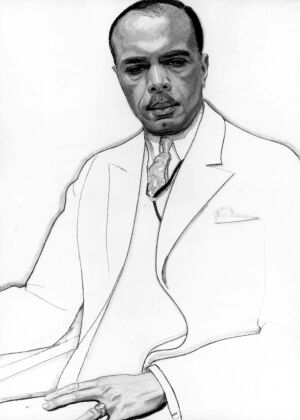

James Weldon Johnson

James Weldon Johnson was an African-American poet,

novelist, public school teacher, principal, diplomat, critic, historian,

journalist, and lyricist. He founded the first African-American

newspaper, the Daily American and was the first national

executive secretary of the National Association for the Advancement

of Colored People. He served as U. S. Consul to Venezuela and Nicaragua.

Johnson is, in literary circles, associated with the Harlem Renaissance. Johnson was born June 17, 1871 in Jacksonville, Florida. His mother was a long time school teacher at an all-black school, and his father was headwaiter at the Saint James Hotel. The young Johnson learned to read at an early age, not surprising given his mother's work. Johnson attended the preparatory division of Atlanta University beginning in 1887. (The school was founded in 1869 after the Civil War by the American Missionary Association, a New England organization.) It was during his first year at college that he began writing poetry. In 1888, Johnson was unable to return to Atlanta because while he was visiting his hometown, Jackson, the city was quarantined due to a yellow fever epidemic. Johnson thereupon acquired a tutor with whom he studied Greek and Latin. Johnson returned to Atlanta in 1889 and resumed his education. During two summers of his college years, Johnson taught in rural Georgia schools. After graduating from the college division of Atlanta University in 1894, Johnson taught for a year at the Stanton School in Jacksonville, his old grammar school, and the school where his mother had taught for many years. Then, at the age of twenty-three, he became its principal. Before leaving Stanton, Johnson had decided to try his hand as an editor and publisher. With savings and borrowed money he founded the Daily American, a daily newspaper serving the black community in Jacksonville. The paper folded eight months later leaving Johnson in debt. In 1896, after the demise of the Daily American venture, Johnson took up the study of law with Thomas A. Ledwith, a white Jacksonville attorney. After six months of study Ledwith had Johnson doing much of the office paper work and the next year suggested that he take the bar examination. The only black lawyers in Jacksonville had been admitted to practice in the Federal courts during Reconstruction, and by that route, to practice in Jacksonville. No black lawyer had been admitted directly by examination in Florida. Johnson describes the events as follows:

[James Weldon Johnson, Along This Way: The Autobiography of James Weldon Johnson 141-144 (New York: Viking Press, 1933)] In the late 1890s, Johnson began writing songs with his brother John Rosamond Johnson who had studied at the New England Conservatory of Music. The music work took the brothers to New York, where they spent much of their time in the following years as their musical work became successful. In the early part of 1900, Johnson and his brother Rosamond, collaborated on an anthem titled "Lift Every Voice and Sing," commemorating Abraham Lincoln's birthday. As African-American groups around the country begin to adopt the song became know as "The Negro National Anthem." In 1901, the Stanton School burned down in a fire that swept Jacksonville, and Johnson used the occasion to resign his position at the school and move to New York City to pursue his work with his brother. Johnson's song writing and his brother's musical performances of their Tin Pan Alley music produced some of the most popular songs of the time. Rosamond and a partner performed the music all over the United States and with Johnson, they toured Paris and London. Johnson, still restless and unsatisfied by his success as a song lyricist, became a student at Columbia University, where he studied English literature from 1901 to 1904. Johnson became involved in the 1904 Presidential campaign and through contacts he made in that work ended up with an appointment as US Consul at Puerto Cabello, Venezuela which he undertook in 1907. It was not a difficult position, and it allowed Johnson to spend much of his two years in Venezuela writing. In 1909, having failed to secure a more prominent posting, he became consul in Corinton, Nicaragua, a post he held for three and a half years. In 1913, with the election of President Woodrow Wilson, Johnson was unable to secure re-assignment to a new post and resigned from diplomatic service. In 1912, Johnson published, anonymously, The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man, a novel which grew out of his English studies at Columbia. Titled an "autobiography" it was actually a novel, although it drew heavily from his own experiences, and still more directly on those of a close friend. The novel was not issued under Johnson's own name until 1927, when it was finally given recognition. Johnson had, even as a young man, had in mind being a journalist and he took up that career again in 1914 as contributing editor with a weekly column for the New York Age, an African-American weekly. In 1916 Johnson became field secretary of the NAACP, which was founded in New York City in 1909. He was appointed Secretary of the NAACP in 1920 and spent the next several years lobbying NAACP issues on Capitol Hill, including a Federal anti-lynching law. Johnson, while at the NAACP, played a significant role in making the NAACP a clearinghouse for civil-rights cases. The 1920s in New York City saw the emergence of what has come to be called the Harlem Renaissance, and as poet, lyricist, and seasoned statesman, Johnson was a primary figure in the movement. In 1931, Johnson was named Professor of Creative Literature at Fisk University and continued in that position until his death. James Weldon Johnson was killed in an automobile accident in 1938. While at Fisk, Johnson completed and published his autobiography, Along this Way, which was published in 1933. James

Weldon Johnson

James

Weldon Johnson (1871-1938)

James

Weldon Johnson: A Brief History African-American

Poets Past and Present: A Historical View Bob Cole, J. Rosamond Johnson, and James Weldon Johnson Poems [Lift Every Voice and Sing] [O Black and Unknown Bard] [The Creation]

Poetry James Weldon Johnson, Fifty Years and Other Poems (Boston: The Cornhill Pub. Co., 1917)(New York: AMS Press, 1975) [online text] [online text] __________________, God's Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse (New York: Viking Press, 1927)(Viking Press, 1932)(Viking Press, 1956)(Viking Press, 1971)(New York: Penguin Books, 1976) __________________, Saint Peter Relates an Incident: Selected Poems by James Weldon Johnson (New York: Viking Press, 1935) __________________, Saint Peter Relates an Incident of the Resurrection Day (New York: Viking Press, 1930)(New York: AMS Press, 1974)(New York: Penguin Books, 1993) Autobiography James Weldon Johnson, Along This Way: The Autobiography of James Weldon Johnson (New York: Viking Press, 1933)(New York: Penguin, 1941)(New York: Da Capo Press, 1973) Writings The Making

of Harlem James Weldon Johnson, The Autobiography of an Ex-Coloured Man, James Weldon Johnson (1912)(New York: Hill and Wang, 1960) [online text] __________________, Self-Determining Haiti (New York: The Nation, 1920) [online text] __________________ (ed.), The Book of American Negro Poetry (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1922)(1931) [online text] [online text] __________________ (ed.), The Book of American Negro Spirituals (New York: Viking Press, 1925)(musical arrangements by J. Rosamond Johnson) __________________, The Second Book of American Negro Spirituals (New York: Viking Press, 1926) __________________, Native African Races and Culture (Charlottesville, Virginia, 1927)(26 pgs.) __________________, Black Manhattan (New York, A.A. Knopf, 1930)(New York: Atheneum, 1968)(New York: Arno Press, 1968) __________________, Negro Americans, What Now? (New York: Viking Press, 1934)(Viking Press, 1938)(New York: Da Capo Press, 1973) James Weldon Johnson & J. Rosamond Johnson, The Books of American Negro Spirituals, including The Book of American Negro Spirituals and The Second Book of Negro Spirituals (New York: Viking Press, 1940) Sondra Kathryn Wilson (ed.), The Selected Writings of James Weldon Johnson (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995) Bibliography Harold W. Felton, James Weldon Johnson (New York: Dodd, Mead, 1971) Robert E. Fleming, James Weldon Johnson (Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1987) Robert E. Fleming, James Weldon Johnson and Arna Wendell Bontemps: A Reference Guide (Boston: B.K. Hall & Co., 1978) Eugene Levy, James Weldon Johnson: Black Leader, Black Voice (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1973) Lawrence J. Oliver & Kenneth M. Price (ed.), Critical Essays on James Weldon Johnson (New York: G.K. Hall & Co., 1997) Bibliography: Essays, Articles, & Bibliographies James

Weldon Johnson: Selected Articles Indexed Lynn Adelman, A Study of James Weldon Johnson, 52 (2) Journal of Negro History 128-145 (1967) Herbert Aptheker (ed.), Du Bois on James Weldon Johnson, 52 (3) Journal of Negro History 224-227 (1967) "James Weldon Johnson," in Stephen H. Bronz, Roots of Negro Racial Consciousness—The 1920s: Three Harlem Renaissance Authors 18-65 (New York: Libra Publishers, 1964) Anne Carroll, Art, Literature, and the Harlem Renaissance: The messages of God's Trombones, 29 (3) College Literature 57-80 (2002). George E. Copeland, James Weldon Johnson—A Bibliography (Master's thesis, School of Library Science at Pratt Institute, Brooklyn, New York, May 1951) Thadious Davis, "Southern Standard-Bearers in the New Negro Renaissance," in 2 The History of Southern Literature 291-313 (1985) Howard Faulkner, James Weldon Johnson's Portrait of the Artist as Invisible Man, 19 (4) Black American Literature Forum 147-151 (1985) Robert E. Fleming, The Composition of James Weldon Johnson's "Fifty Years," 4 (2) American Poetry 51-56 (1987) ______________, Contemporary Themes in Johnson's Autobiography of an Ex-colored Man, 4 Negro American Literature Forum 120- 124 (1970) William E. Gibbs, James Weldon Johnson: A Black Perspective on "Big Stick" Diplomacy, 8 (4) Diplomatic History 329-347 (1984) Donald C. Goellnicht, Passing as Autobiography: James Weldon Johnson's The Autobiography of an Ex-Coloured Man, 30 (1) African American Review 17-33 (1996) Martin Japtok, Between "Race" as Construct and "Race" as Essence: The Autobiography of an Ex-Coloured Man, 28 (2) Southern Literary J. 32 (1996) Kenneth Kinnamon, "James Weldon Johnson," in Dictionary of Literary Biography 168-181 (Vol. 51) Richard Kostelanetz, The Politics of Passing: The Fiction of James Weldon Johnson, 3 (1) Negro American Literature Forum 22-24, 29 (1969) Julian Mason, "James Weldon Johnson," in Joseph M. Flora & Robert Bain (eds.), Fifty Southern Writers After 1900 280-289 (New York: Greenwood Press, 1987) Arthenia Bates Millican, James Weldon Johnson: In Quest of An Afrocentric Tradition for Black American Literature (Doctoral dissertation, LSU, 1972) Lawrence J. Oliver, Writing from the Right during the "Red Decade": Thomas Dixon's Attack on W. E. B. DuBois and James Weldon Johnson in The Flaming Sword, 70 (1) American Literature 131-152 (1998) Saunders Redding, "James Weldon Johnson," in Louis D. Rubin, Jr. (ed.), A Bibliographical Guide to the Study of Southern Literature 228-229 (Baton Rouge, Louisiana State University Press, 1969) Cristina L. Ruotolo, James Weldon Johnson and the Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Musician, 72 (2) American Literature 249-274 (2000) Charles Scruggs, "H. L. Mencken and James Weldon Johnson: Two Men Who Helped Shape a Renaissance," in Douglas C. Stenerson (ed.), Critical Essays on H. L. Mencken (Boston: Hall, 1987) Joseph T. Skerrett, Jr., Irony and Symbolic Action in James Weldon Johnson's The Autobiography of an Ex-Coloured Man, 32 (5) American Quarterly 540-558 (1980) Thelma B. Thompson, Autobiography as Self-Discovery and Affirmation in James Weldon Johnson's Journey, Along This Way, 21 (1) Afro-Americans in New York Life and History 47-58 (1997) Research Resources James

Weldon Johnson Papers J. Rosamond Johnson Web Resources: Harlem Renaissance Poets of the Harlem Renaissance and After The Harlem Renaissance: Black American Traditions Harlem

Renaissance The Harlem Renaissance and the Flowering of Creativity Cultural Contexts of the Harlem Renaissance Alabama Voices from the Harlem Renaissance The

Harlem Renaissance Women of the Harlem Renaissance Langston Hughes and the Harlem Renaissance The Harlem Renaissance and Leftism: African American Publication in the 1920s and 1930s Harlem: Mecca of the New Negro-1925. Harlem Renaissance Bibliography Harlem Renaissance: Selected Bibliography Harlem

1900-1940: An African-American Community

|